Prognosis is a slippery science. Insofar as it is science, it relies on understanding how something will play out under different sets of conditions - with or without a medical intervention, for example. You need to understand the natural history of the disease, and then understand how an intervention might alter that natural history for the specific patient in front of you.

You also need to discern if the patient in front of you is enough like the other patients you’ve seen and the subjects in the trials upon which you’re relying. You can’t determine most outcomes with certainty and nevertheless you must act. If we could, we’d just need algorithms, but as it is, we need wisdom. Over-reliance on algorithms is unwise to the extent that the individual patient under your care doesn’t fit the evidence that informs the algorithm.

There are plenty of resources out there to help guide clinicians in offering more accurate prognoses, like ePrognosis, QxMD Calculate, MDCalc, and Colorado Program for Patient Centered Decisions, in addition to the primary medical literature. I’m not going to focus on specific prognoses here. Instead, I want to highlight how we talk about prognosis and how we might do it better.

Holistic Prognosis

“What have your doctors told you about what you might expect in the time ahead?”

I ask most of my patients this question at one point or another. I usually get one of two answers:

“Not much.”

A time-based prognosis, e.g., “They say I’ve got six months.” This usually contains an exact number. Sometimes “the docs don’t know,” but that’s also usually in reference to a time-based prognosis.

What I see documented in notes isn’t much better. Clinicians write things like “I told the patient this was incurable but treatable,” or “Guarded prognosis.” These things, if conveyed to the patient, aren’t helpful in influencing a patient’s understanding of their disease or prognosis. Reading the notes in the chart, I, too, am no better informed. Is there a difference between a guarded, limited, and poor prognosis? What is the timeline of the prognosis? What will the patient’s experience of that time be like? These are vague shibboleths, shyly gesturing toward the limits of medical intervention without formal acknowledgment.

After asking my question, I spend some time exploring what the patient’s own perception of the future looks like - their hopes and their worries. In addition to helping the patient articulate these things for their own sake, I’m gauging how aligned these three parties are (the patient, their other clinicians, and myself) so I know how to calibrate what I might tell them. For someone who shares my same worries about the future, what I’ll share will be less jarring than if someone has a hope of total recovery. Those two conversations will look very different.

Then I’ll ask permission if I can share my own thoughts. I always ask permission, and if I get anything other than a “yes,” it’s a no. If they keep talking about their cousin’s home remedy for cancer, I don’t push forward. They haven’t given me permission to do so yet. So I’ll circle back around and figure out what we need to talk about in order to make moving forward okay for them.

A quick aside here: what happens when someone doesn’t give you permission? “Doc, I don’t want to talk about any of that right now. We need to stay positive.” Maybe there’s time to leave things alone for now, but maybe there’s not. There are certain aspects of this that someone can’t ignore. For example, if their impending decline is going to require a lot of changes at home for those who live with them, they’re doing their family a disservice to keep them in the dark. I’ll ask permission to speak with their family without them, if need be.

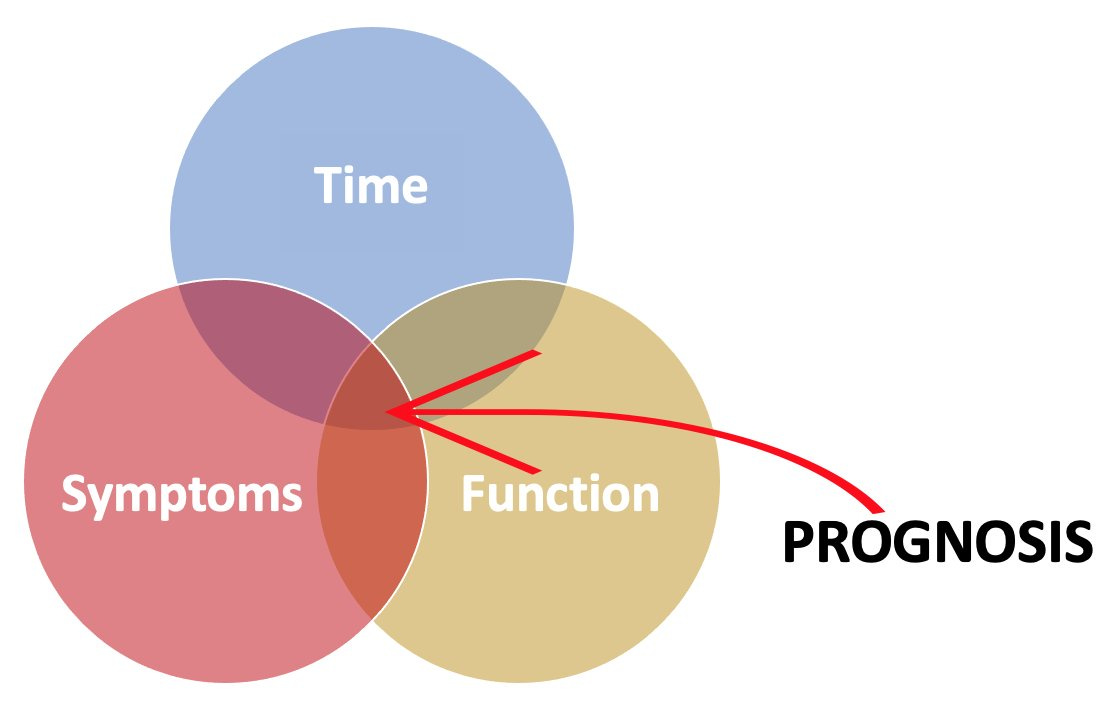

That brings us to an important point: prognosis is a lot more than a prediction about life expectancy. It does someone little good to believe they have six months left to live and assume they’ll carry on through those months as fit as they are the day you talk with them. That’s probably not the case for most people with serious illness. A holistic prognosis includes what we believe the future holds for someone’s function and symptoms, as well as how long their life might be. Any given conversation can focus on all three of these or just one or two.

Time. If clinicians share any prognosis, it’s this portion of it. Usually it’s some specific number: “You’ve got three months left.” I’ve never seen someone predict a life expectancy so far out with reliable accuracy. Instead, I stick to ranges: years, months to a year, weeks to months, days to weeks, hours to days, minutes to hours. I humbly admit that I’ve been wrong on either end: someone might live longer or shorter than I predict, but generally, the shorter the prognosis becomes, the more accurate I am. For some chronic conditions, this is the least relevant portion, as someone probably has decades of life remaining, but can expect other serious changes in their symptoms and functioning (e.g., schizophrenia, multiple sclerosis).

Function. As serious illnesses progress, people may experience a steady decline in their functioning and gradually lose the capacity to engage in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) and activities of daily living (ADLs). Alternatively, there may be periods of acute exacerbation requiring hospitalization and rehabilitation from which they bounce back (but maybe not as robustly each time). They’ll need more caregiving support. They’ll need special accommodations at home or else need to move somewhere else. They’ll eventually need some kind of equipment to function properly (e.g., feeding tube, wheelchair). They’ll need to adapt to their hobbies or find new ones. They’ll need accommodations at work or else retire early. This aspect of prognosis is a big deal.

Symptoms. Many people might perceive a time-based prognosis differently depending on what they would expect from their symptoms. It’s not just that symptoms can wax and wane and sometimes become permanent. It’s also that the tradeoffs necessary to manage symptoms usually become more extreme as someone becomes sicker and more frail. Medications can carry adverse effects, but effects that were once intolerable may become acceptable if the symptom they treat has worsened.

Talking About Prognosis

You can provide all the information in a holistic prognosis and still leave the patient and their family scratching their heads. I find this happens when clinicians start citing statistics for things that aren’t clear-cut. The most helpful probabilities are usually 0% and 100%, but how common is it that we can be so certain? If we can say it, it helps to do so. Otherwise, saying someone has a 30% chance of this if they do X and a 50% chance of that if they do Y is an unwieldy way to help with decision-making. Perhaps we do this because we feel like someone can’t trust us. We don’t have a well-established relationship with them or we’ve been trained to just offer the patient a menu of choices, so at least we can trust the numbers together. There are a number of problems with this approach.

First, it’s challenging to extrapolate what we know from clinical trials to the patient in front of us. If an oncology clinical trial demonstrated a 60% radiologic response rate, what does that mean for the patient you’re talking to right now? Well, radiologic response rate is a surrogate endpoint, so you’d first need to ask if that endpoint, for that cancer and that treatment, has been validated - does it actually correlate with a clinical outcome like overall survival or improved symptoms? Let’s say response rate is validated in this particular instance, so you can feel confident if you see changes on their CT scan, that tracks with a change in their survival or symptoms. Nevertheless, it’s an extrapolation to take population-level data and claim it applies to an individual. Study populations do better than real world patients, the outcomes might not generalize to the patient in front of you, and the real world outcomes, particularly if the trial is novel, may regress to the mean. That doesn’t mean it’s wrong to extrapolate, only that citing statistics from trials might not be the best way to proceed with supporting someone’s decision-making.

Second, numbers don’t help patients as much as we think they might. Patients take the numbers we give them and transform them into “decision weights” - this is either going to happen, probably will/won’t happen, or won’t happen. They also bring their own heuristics to the decision-making process which may lead them to believe that there’s either a 100% or 0% chance of them actually being in the group you cite. So if you say there’s a 1% chance of an outcome occurring, based on a person’s mood, worldview, religion, and personal experiences, they may believe there’s a 100% chance of being in that 1%. Your numbers actually didn’t help them make the decision. I’m not saying we should build choices to block out a patient’s own approach. Numbers just don’t provide the clarity we think they do.

Third, numbers get complicated really quickly, and we often don’t have them all. Let’s take a decision about whether or not to start an antibiotic for pneumonia. If the patient is ambivalent about treatment and wants to know the burdens and benefits, and you’re inclined to share numbers, then you’ll need to cite the probabilities of success and adverse effects with and without treatment. You might want to cite probabilities of individual adverse effects, including death. At the end of the conversation, you might be juggling a dozen or more numbers. I provided an absurd example, but the same thing occurs when just a few numbers are cited too. How are these weighted against one another? How do you compare, say, a 20% chance of death against a 40% chance of arrhythmia (10% chance its serious) against a 60% chance of dizziness against a 30% chance of spontaneous resolution of the issue, etc.? Furthermore, when you dig into these numbers, they might be gleaned from trials with small populations and you might not have the real world surveillance data on them all. You might be able to provide numbers for some outcomes but not for others. Why would we go so far as to provide these numbers (imperfect as they are) and not provide a way patients could compare them with one another? And yet we can’t do that; the legion of numbers that could overrun any medical decision doesn’t help decision-making all that much.

Sometimes we veer in the other direction: we limit the use of numbers but rely on vague tropes, like the one I mentioned above: “it’s not curable but it’s treatable.” For someone with metastatic pancreatic cancer, for example, that’s true. It provides necessary information in the smallest possible quantity (“it’s not curable”) with a rapid chaser of hope (“but it’s treatable”). If we unpack “treatable,” though, we find a world of unspoken prognostic information. There may be multiple lines of systemic therapy, maybe surgery, maybe radiation, and certainly a threshold upon which no further treatment will be available. One’s life will be shorter, much shorter, than expected. To speak of all that at an initial visit would be overwhelming, but seeing the whole landscape, if only briefly, can help orient patients to their care and the milestones at which they’ll have crucial decisions to make in the future.

So, if we’re going to try to minimize the use of statistics and vague gestures in our conversations with patients about prognosis with the hope that we can help them make better decisions about their healthcare, what do we do instead?

We discuss the best case, the worst case, and the most likely case scenarios down different paths (referred to here as BCWC, but don’t forget it also includes the most likely case scenario too). A team at University of Wisconsin developed this wonderfully simple framework for surgery and have since built it out to include dialysis and ICU admission. I find it applies just as well to medication initiation, discharge to a nursing facility versus home, and almost any scenario where we’re comparing interventions or an intervention against no intervention.

What are the advantages here? First, BCWC integrates what we know from trials, real world surveillance, and our clinical experience into a seamless story. We can still humbly admit that we can’t predict the future with perfect accuracy and sometimes the real outcome might be better than the best (or worse than the worst) we predicted. The story is important because we think in stories; we don’t live our lives jumping from probability to probability. How often has a patient used “my family member did this and that happened…” as a reason to accept or decline a treatment? That story may have influenced their decision more than your statistics! I still provide the numbers I can if patients ask me directly for them, but always in the context of a story.

Second, holistic prognosis is built into BCWC. In the course of telling stories about the best case, worst case, and most likely case scenarios, you’ll need to tell more than mere timeframes. You’ll need to avoid vague phrases. You’ll need to describe what that time looks like, envisioning function and symptoms.

Third, BCWC wakes you up to the limitations of surrogate endpoints. As you’re gathering your thoughts beforehand about how to talk about these different scenarios with someone, you might find it’s silly to build a whole scenario on a surrogate endpoint. “The best case scenario is that your hemoglobin A1c improves,” or “The worst case scenario is that we see the tumor is larger on your next CT scan.” These things only mean something insofar as they’re connected to things that actually impact someone’s life. The best case scenario for a reduced A1c is a lower risk of cardiovascular events, death, dialysis, and so on. The worst case scenario for cancer growth is death, disability, or worsened symptoms. This helps to keep us honest about our appraisal of the evidence: do we really think that trial on which we’re basing our recommendation is going to influence any meaningful outcome for the patient before us? That doesn’t mean we throw surrogate endpoints out the window. Instead, we can situate their humble position within the BCWC if they can track with meaningful clinical outcomes. If they can’t, then we need to ask ourselves why we’re relying on them.

Fourth, BCWC is flexible to changes over time. Let’s say you use BCWC to talk to a patient about intubation for respiratory failure. They’ve chosen intubation and in the subsequent days, their health deteriorates further. Now you can have another discussion with their family, again relying on BCWC, about different decisions. This repeated use can emphasize to those with declining health than the tradeoffs in pursuit of certain goals will become more significant as their disease progresses - the most likely scenario may inch nearer the worst case scenario as time goes by. If we move upstream, in less dire circumstances, it helps to teach patients that outcomes are uncertain, and we can develop contingency plans for undesired outcomes. Each new decision and change in health status brings people to still more forks in the road where BCWC remains useful.

Fifth, BCWC is flexible across settings. We often think of discussing prognosis when someone is facing the end of their life, but people need to have some idea about the future in all sorts of other settings. What’s the BCWC for different treatment options in a new diagnosis of schizophrenia? What’s the BCWC in choosing between insulin or other ways of managing diabetes? What’s the BCWC for a vaccination versus no vaccination? This doesn’t mean you need to use it for every single clinical decision, but it can be helpful for those decisions in which patients are struggling with some measure of ambivalence. Before long, you may find yourself thinking in these terms even if you’re not explicitly using it with every patient.

Sixth, BCWC provides good scaffolding for incorporating a patient’s goals of care. If you’ve already discussed longevity, function, and comfort, and have some idea of how someone prioritizes their healthcare goals, then you can use BCWC to show what will impact those goals. For example, death may not be the worst case scenario for some people.

Seventh, BCWC helps resist escalation of commitment. Also known as the “sunk costs fallacy,” this occurs when we allow past investments to influence future decision-making despite worsening outcomes. This taps into cognitive biases like loss aversion and plan continuation bias, as well as our general optimism. However, using BCWC to recognize that a certain intervention may not yield the desired outcome and to discern some possible limits in intervening help to check these biases so that folks don’t get caught on a conveyor belt of unwanted and unhelpful healthcare. They may make difficult decisions before hand by setting limits, but even if they don’t, they become acquainted with talking about uncertainty and undesirable outcomes.

Parting Thoughts

Prognosis is tough. We’re not clairvoyant, and so we do the best we can to offer some insight into what might happen using the murky crystal ball we do have: our knowledge of the published evidence combined with our clinical experience. Prognostication isn’t about throwing a bunch of numbers at a patient and letting them sort through them like a psychic reading tea leaves. It’s about helping them pursue what matters most amidst uncertainty and planning for different outcomes. Even if we don’t identify the exact outcome that actually occurs, the conversation itself can have a sobering effect as people face the reality of their frailty and mortality in these scenarios. This provides a good lead-in for another conversation. As you share these different scenarios, you might follow-up by saying, “Given these worries about what could happen even in the best case scenario, it might be a good idea to discuss some emergency backup plans. Can we do that now?” A topic for another time…

Trajectories

Following a meandering reading-path, sharing some brief commentary along the way.

“Behavioral epidemic of loneliness in older U.S. military veterans”

Loneliness is common in this sample and associated physical and mental health problems. The question is, if you discover your patient is lonely, what can you do about it? Well, I’m not entirely sure, but GeriPal has a good way to kick off your pondering with this podcast. We can start be differentiating between social isolation and loneliness, and then discerning how someone might be lonely (e.g., lonely within their marriage, lonely in their work, etc.).

“Daily physical exams in hospitalized patients are a waste of time” and “Routine daily physical exams add value for the hospitalist and patient”

A point-counterpoint on the utility of the daily physical exam in the practice of general hospital medicine. I can empathize with the “waste of time” perspective, as a physical exam used as a screening instrument for a hospitalized patient is probably very low yield. Why screen the heart every day via auscultation if the patient is admitted for cellulitis and not, say, the cranial nerves? One is just as likely as the other to change from day to day. That isn’t to say you shouldn’t do a targeted, hypothesis-driven exam. However, I also empathize with the “valuable” perspective because in order to be good enough to detect subtle nuances in physical exam findings, you need to see a lot of normal exams, and so the daily physical exam provides that opportunity to hone one’s practice.

Aimee Walleston remarks on the irony that COVID-19 has revealed how medicalization has influenced both those in favor of vaccinations and those against. The pandemic is certainly a medical problem, but it’s also more than a medical problem. Yet when you’ve got a hammer, everything looks like a nail. And when you start hitting things that aren’t nails with a hammer, you’re going to cause a lot of damage.

“Should regulatory authorities approve drugs based on surrogate endpoints?”

Surrogate endpoints exist so that clinical trials can produce useful data more quickly. However, when researchers start using endpoints that aren’t validated (that is, they haven’t been shown to correlate with any meaningful clinical outcome like survival or symptoms), their usefulness wanes tremendously. Nevertheless, regulatory agencies like the FDA in the United States are relying more on these surrogates and failing to enforce the follow-up confirmatory studies that should use the clinical outcomes.

“Not every question has a scientific answer”

COVID-19 have revealed that science is only part of the puzzle in responding to the pandemic. It’s not as easy as “following the science.” Decisions about what to do and when are value-laden and are subject to the democratic processes of debate and scrutiny. For those with a certain epistemology, though, science would be used to bludgeon those who disagree with a certain point of view. That’s not the best use of science.

Poking fun at communication maps and techniques. Less humorously, though, I’ve seen similar interactions when clinicians over-rely on those communication maps, forcing interactions through a particular algorithm or failing to pay attention to the situation and the person in front of them.

Ben Frush, a medical resident, shares his perspective on the often mechanical approach to caring for dying people in the hospital. The way the piece is written pulls off the mask of the promises of medicine to reveal the limits underneath - for example, in repeatedly mentioning that he’s ordered comfort. As if a doctor’s order could bring comfort so easily. The essay also reveals that the hidden curriculum, at the bedside and in the call room, is far more formative than any experience we might have in the classroom.

“Functional trajectories among older adults before and after critical illness”

These authors tracked patients after they were discharged from the ICU and discovered that those with pre-morbid disability were likely to lose more function after their stay in the intensive care unit. Indeed, they may not ever return to their baseline. One thing that’s absent from the study is information about discharge destination and goals of care. For some, they may have opted for a comfort-focused plan of care and gone home which would have influenced the results. For others, they may have gone to a nursing facility for rehabilitation. Some people don’t do well in rehab, but within the boundaries of the trial, it would have been helpful to know if these two sub-populations fared differently and in what ways they did so.

“Is nudging patients ethical?”

A GeriPal podcast discussion with Jenny Blumenthal-Barby and Scott Halpern at the intersection of behavioral economics and clinical decision-making. They specifically focus on “nudging,” which is the use of decision psychology and behavioral economics to influence decision-making without coercion. Over the course of their conversation, they make the case that clinicians are inescapably “choice architects.” There is no neutrality in how we help our patients make decisions. If that’s the case, how do we help our patients without being coercive? They don’t have any great answers during the episode, but it sounds like rather than a technique, we need to develop within ourselves reliable traits that would steer us, as clinicians, toward the good and away from the bad; we need, in a word, virtue.

“Of course hospitals in crisis mode should consider vaccination status”

Law professor Teneille Brown argues that COVID vaccination status should be an important factor into allocating scarce resources amidst crisis standards of care. As far as I know, once you become severely ill and in need of a ventilator or ECMO, it’s not clear that vaccination status influences outcomes. I’d be interested to know if such data exists. We veer into dangerous territory when we start to use criteria that aren’t clinically relevant for allocation of scarce resources. People with health conditions that can be even remotely linked to personal responsibility are already stigmatized. We shouldn’t compromise access to healthcare, even in a crisis, using that as the (or a) criterion. Unless we can establish the clinical relevance of vaccination status during critical illness from COVID, then using it as a criterion for scarce resource allocation appears like an indictment of personal choice and opens the door for all kinds of arbitrary denial of healthcare. The impulse to use healthcare as a cudgel (or carrot) is always present; we need to guard against it.

“What’s wrong with advance care planning?”

These authors argue well that advance care planning (ACP), specifically the creation of advance directives (AD), just doesn’t have the effect we would hope. It doesn’t help surrogate decision-makers with tough decisions and there’s no evidence that it improves goal-concordant care. Speaking for myself, I’ve never raised an AD high in an hour of need, a beam of light shining down on the document, and all the dilemmas were resolved and anxieties washed away in a situation with complex decision-making. But what if AD are helpful in another, less-easily-measurable way? What if it’s affectively, existentially beneficial to contemplate your frailty, dependence, and mortality (which the AD leads you to do), and that influences how you make decisions even before you lose the capacity to do so? If so, then the AD is a very, very poor modern day substitute for the ars moriendi. Maybe we can think of better ways to promote meaningful spiritual and existential growth as someone faces serious illness and death? Because even if they survive, even if they live for another twenty years, it will be after they’ve realized they walk in the shadow of their own death.

“Risk of suicidal self-directed violence among US veteran survivors of head and neck cancer”

The risk of suicide in patients with head and neck cancer is higher than other cancers, and much higher than the general population. This study helpfully adds to our knowledge here by showing that most suicide attempts occur within months to a year of diagnosis (that’s probably when the most morbid aspects of treatment occur), though it can occur years out too. There are unsurprising pre-cancer risk factors that heighten the risk (e.g., chronic pain, mood disorders). Perhaps most surprising, and something that will be hard to establish in a prospective trial, is that while mental health referrals did not reduce suicide attempts, a palliative care referral within 90 days of diagnosis did!

L.M. Sacasas writes insightfully about the formative nature of technology at his newsletter The Convivial Society. Here, he reflects on the emotional distance that social media interposes between people thus degrading their capacity to empathize and, yes, pity one another. This diminished the quality of our conversations and could be forming us to be less compassionate people. As more discussions about medicine move online (e.g., professional societies, Twitter), this is something clinicians need to keep in mind too.