Rita Charon tells a story of a medical student defeated by his delirious patient, unable to get all the details from the history and physical exam he would need to inform a robust assessment and plan: “Instead of feeling compassionate and helpful toward her, he felt only angry and fed up. He had been reduced by this night on call and blamed the patient for his failure.” This patient was, as most clinicians would recognize, a “poor historian.” These patients don’t or can’t tell a story that the clinician can then easily translate into a disease script. But who is the historian of the medical encounter? Who’s responsible for compiling all the relevant information from the patient’s perspective as well as the clinician’s? It’s not the patient. The clinician is the historian.

Caring for uncooperative patients is a formative experience, as Charon recognizes:

“Paul was being dehumanized by the process of caring for this patient. The stringent requirements made upon him by the structure of the teaching hospital dictated that he express the medical history from this woman at all costs, resort to violence in obtaining the lab data, and internalize his resentment for her for being an imperfect patient. […] Medical training teaches students to substitute the impressions, agendas, and requirements of the physicians for the impressions, requests, and needs of the patients.”

Charon’s answer to this dilemma is to ask that her medical student write a fictional account, from the first person perspective, of his patient’s experience, starting before her arrival and leading up to their time together in the hospital. The challenge for clinicians is to “learn to empathize without losing their objective stance. […] Writing fiction calls forth this power of simultaneous identification and distance.”

Charon elsewhere argues that narrative pervades the clinical encounter. It’s inescapable:

“What is it that doctors and patients do together? Study of their language reveals that they are engaged in deep conflict about meaning and purpose. […] Doctors use words to contain, to control, and to enclose. […] Patients use language to express the sensations of things being amiss. […] Because patients don’t know how (or in what) to contain the sensation, they use language to express multiple levels of knowledge: thoughts, feelings, descriptions, associations, metaphors, guesses about causality, and reports of their own behavior in trying to manage the problem. Rather than categorizing and reducing, patients enlarge and embroider.”

It’s hard enough to tell a good story, harder still to tell it with someone, and harder even still when you both use language differently, as in the clinical encounter. The language barrier presents its own challenge, but so too is the clinician’s self-understanding as a co-author. If they remain ignorant of their intimate involvement in this story that patient and clinician are telling together, then they’re liable to step over (or on) important details.

This accords with Anatole Broyard’s own musing as he faced metastatic prostate cancer: “In her essay ‘On Being Ill,’ Virginia Woolf wondered why we don’t have a greater literature of illness. The answer may be that doctors discourage our stories.” That literature has grown substantially since Woolf’s own time, but the point remains: in an effort to extract from the patient’s story the secrets of the body, a clinician may discard seemingly worthless dross to purify a diagnosis only to also lose the alloy that made sense of the patient’s own experience. “The patient is suffering from terminal interrogativeness,” Broyard opined,

“His soul is fibrillating. […] It may be necessary to give up some of his authority in exchange for his humanity, but as the old family doctors knew, that is not a bad bargain. In learning to talk to his patients, the doctor may talk himself back into loving his work. He has little to lose and everything to gain by letting the sick man into his heart. If he does, they can share, as few others can, the wonder, terrors, and exaltation of being on the edge of being, between the natural and the supernatural.”

If clinicians are historians, then they’re responsible for telling a story - indeed, a good story. The mark of a good story in this case isn’t that it’s entertaining or even educational, but that the story makes sense of what’s going on in this person’s life. That’s a responsibility clinicians share with their patients. This provides what Howard Brody called symbolic healing, which is a way of caring that offers an explanatory system, care and compassion, and mastery and control. “As a general rule, patients will be more inclined to get better when they are provided with satisfactory explanations for what bothers them, sense care and concern among those around them, and are helped to achieve a sense of mastery or control over their illness and its symptoms.” That isn’t to say that these existential boons can cure cancer, but you may have met people for whom “illness remains mysterious and frightening” even if benign, and it had a disproportionate impact on their life. Alternatively, patients with dire health problems can approach them with equanimity because of symbolic healing.

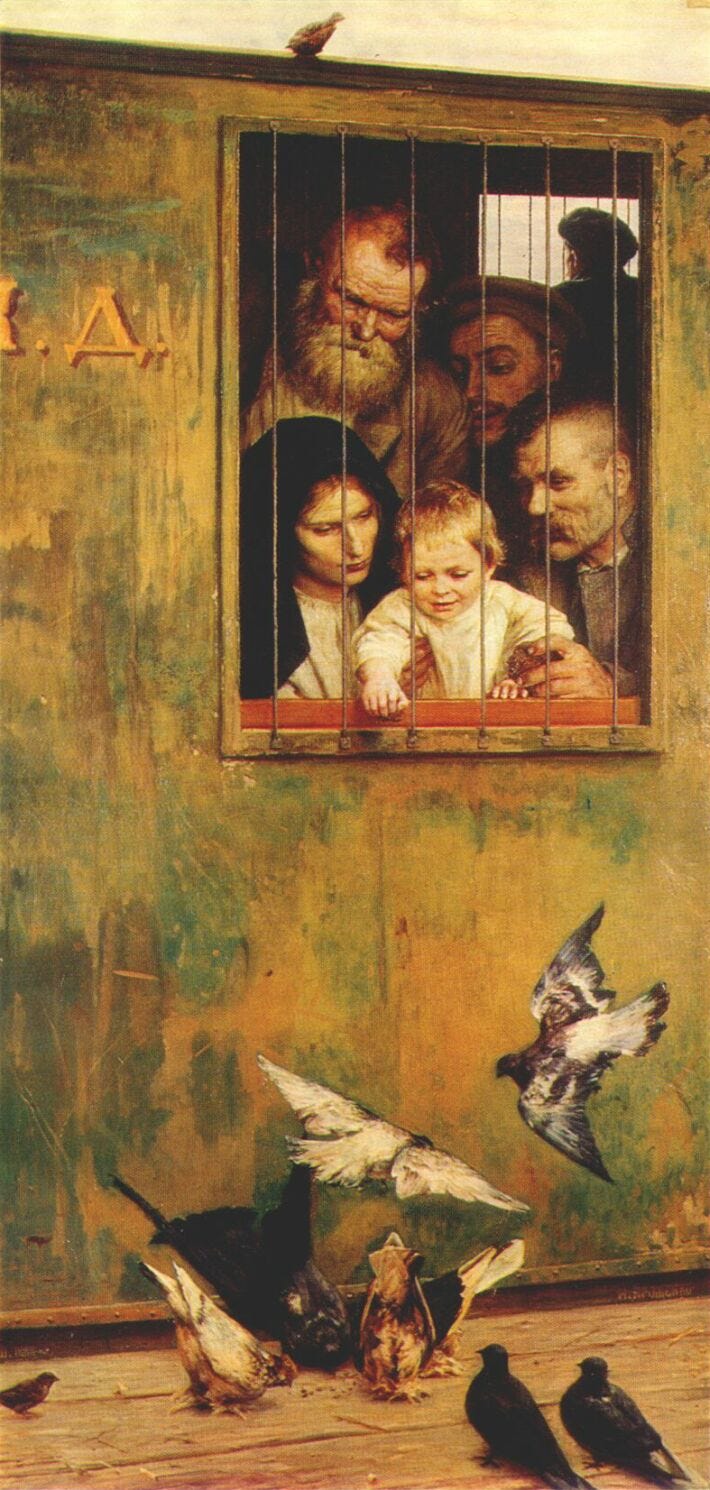

I would add that another aspect of symbolic healing is helping to restore people to their stories. What is happening or has happened may inflict terrible changes on their body, but it remains their body, their life, and their story, so what are they to do with it now? This often isn’t achieved because clinicians fail to appreciate how much patients belong to their own stories, traditions, and communities. Consider this scene from Fidelity by Wendell Berry, which describes a pillar of the family and local community now dying under the burden of too much medical technology:

“Burley remained attached to the devices of breathing and feeding and voiding, and he did not wake up. The doctor stood before them again, explaining confidently and with many large words, that Mr. Coulter soon would be well, that there were yet other measures that could be taken, that they should not give up hope, that there were places well-equipped to care for patients in Mr. Coulter’s condition, that they should not worry. And he said that if he and his colleagues could not help Mr. Coulter, that they could at least make him comfortable. He spoke fluently from within the bright orderly enclosure of his explanation, like a man in a glass booth. And Nathan and Hannah, Danny and Lyda stood looking in at him from the larger, looser, darker order of their merely human love.”

The task isn’t to love one’s patient like their family loves them. The task is to avoid stepping on that love as we march toward diagnosis and treatment; the task is to help them tell a story of love even amidst this illness.

Looking in at those whom we love and are stricken by illness, we don’t just want symbolic healing though. We want a cure. We want restoration. Another purpose of the history is to provide a story useful for diagnosis, treatment, and coordination of care across multiple clinicians. That’s indisputable. Focusing on the latter can sometimes make us blind to the former, though, which is my concern here.

Pitfalls in the History

It’s interesting that we describe the process of listening to and understanding a patient’s story of illness as “taking” a history. Despite the patient being identified as the historian, this common phrase of “taking” suggests the agency belongs to the clinician. It belies that there are pitfalls in how you might appreciate the story of illness a patient’s life:

Reducing a story to its mere biological details. We are inescapably biological in our existence, thus biological reductionism is handy: it gives an objective (albeit limited) language to talk to anyone about the human experience, it allows us to see ways we can intervene on the human experience (hopefully for the good), and those interventions can be tested empirically. Biological reductionism is very important for a disease-centered practice of medicine but comes up short in a person-centered practice. Medicine isn’t a science; it’s a science-using discipline. As such, there’s more to it than biological intervention, just like there’s more to people than their biology. Careful, though: this also doesn’t mean that we learn about all those other aspects of someone’s life just to bend them in service to the biologically reduced goals medicine is best at manipulating. In training, morning report (case presentations with discussion of details in history, physical exam, labs, differential diagnosis, and treatment) is a biologically reductionistic exercise to sharpen technical acumen.

Valuing one type of testimony over another. Epistemic injustice is a “type of harm that is done to individuals or groups regarding their ability to contribute to and benefit from knowledge.” Specifically, “testimonial injustice happens when a prejudice causes a hearer to give less credibility to a speaker’s testimony and interpretations than they deserve.” Someone suffers testimonial injustice, for example, when their reports of pain are disbelieved because they carry a stigmatized diagnosis. This is codified in the way most clinicians write their progress notes: Subjective-Objective-Assessment-Plan. The patient’s report is subjective - idiosyncratic, limited, opinionated. The clinicians’ report is objective - standardized, neutral, fact. Which testimony, do you think, is given more weight? Even when most clinicians know how important the history is, it’s because they see its importance in service to the translation project of the clinician to secure a diagnosis, rather than restoring patients to their own stories and lives. Clinicians anchor on details they think are important to their translation project and miss other important facets of the patient’s story. This is particularly germane in mental health care, where patient’s accounts of their suffering are filtered either through psychiatric biological reductionism or a dogmatic psychotherapeutic worldview. It’s inevitably that clinicians will help patients tell their stories, but usually the clinician’s story overshadows the patient’s because their testimony is privileged.

The uncanny valley. If everything serves the end of diagnosis and treatment, then the clinician will learn some basic strategies for responding to the patient’s emotion in the clinical encounter. This is important because emotion can inhibit efficient diagnosis or a patient’s adherence to treatment. However, without caring about ends other than diagnosis or treatment, the clinician can just tag these techniques on for the sake of efficiency. Patients can see right through that because reducing compassion to technique stymies the clinician in the uncanny valley. This is a concept borrowed from robotics: the more human a robot appears, the more robust and warm an affective response it evokes from us. One would expect this to be a linear relationship, but actually there’s an experience of revulsion (the uncanny valley) when a robot appears very realistic but not fully human. So too with clinicians who speak empathic words from their checklist: they behave as robots and patients see it. A history told by a robot will be a different history from one told by another human.

Lacking clarity about someone’s baseline. How will we know what healing looks like if we don’t know that to which we’re trying to restore someone? It seems obvious enough that if someone has broken their arm, then fixing the arm is imperative whether they’re a gymnast or a retiree. But as someone becomes frail or seriously ill, the path back to “baseline” may become more perilous. It may even become permanently blocked. Even for the gymnast’s broken arm, there may be unique considerations about her fracture and her activity that preclude or indicate certain surgical maneuvers that would only come to the fore if one knew those “baseline” details.

Being inflexible. This is a pitfall in two places. First, if one can’t form a running differential diagnosis while talking to a patient and modify it on the fly, limiting or expanding on certain questions to refine that differential, then the interview will take longer, be less efficient, and the final differential diagnosis will be less robust. Sometimes inefficiency is the price we pay for building rapport and getting to know someone, but sometimes it’s just a tax paid for poor technique. Second, being unable to veer off your script to explore something that might be more important in that moment than your agenda means you’ll miss important opportunities to learn more about your patient and help them.

A Better History

If you agree that any or all of the pitfalls I just described are problematic, then you may also lament that we just don’t have time to overcome them in the clinical encounter - whether you’re outpatient or inpatient. My hope, though, is that what I’m about to suggest won’t take much longer, but it will make it easier to identify what’s most important and how to address it. Sometimes the issue is obvious: a broken arm or a STEMI. Other times, it’s not obvious or other issues complicate those problems. Either way, because clinicians are co-authors with their patients in helping to write this chapter of their life, clinicians need to be mindful of what they’re doing in the storytelling just as much as in the management of those conditions. So, if I could suggest:

Be curious about the story. Have you ever spoken with someone who clearly wasn’t curious about what you had to say? It probably wasn’t a great conversation. And perhaps you’ve interacted with students who aren’t curious either; they don’t make for great learners. So, there are at least two types of curiosity. The first type is what most have: an intellectual curiosity that drives them through medical training and toward a diagnosis and treatment plan with their individual patient. This is critical for technical proficiency. Without this curiosity, clinicians stop learning, start relying on reflex to manage the clinical encounter, and miss diagnoses. This may happen if the clinician is overwhelmed on a particular day or burnt out. The second type of curiosity is a joyful engagement with a patient’s story. This isn’t intrusive or gossipy, but simply a genuine interest in getting to know their patient for the sake of helping them. While the first type of curiosity helps us to know diseases and treatments, the second type helps us to know people. You need both to be a good historian, and the second is necessary to sustain compassion in the face of repeated encounters with the suffering of others. Charon might call this second type of curiosity “narrative competence.” Reading fiction and non-fiction may help to develop this form of curiosity. The environment of care needs to be sustainable too: someone who is stifled by their workload or anxious about other things in their life will struggle to sustain curiosity.

Be humble in what types of testimony you value. It’s true: sometimes patients provide unreliable information. That was the dilemma for Charon’s medical student. But clinicians, too, can be unreliable. We can be mistaken and there are limits to what medicine can accomplish. Furthermore, sometimes we miss the mark: we think we know the priority (e.g., fixing a broken arm) when really the patient seeks something more (e.g., safety from domestic violence). Without humility, it’ll be difficult to cultivate the trust to work together with patients toward health. A special form of this, epistemic humility, “allows room for balancing clinical evidence, professional judgement, and patients’ perspectives.” It is “a commitment to continuous responsiveness to the patient’s experience and recognition of the limitations of applying clinical expertise to different forms of clinical decision-making.” Such epistemic humility requires frequent reflection on one’s practice. Hold lightly the powers you wield as a clinician.

Believe what you say. As communication training like VitalTalk becomes more popular, we need to believe what we say when we respond to emotion. I can’t say, “This must be hard for you.” That’s just me; maybe you can. That’s not something I would say to a friend or family member. It’s not something that I can say from my heart. This might be a challenge for many clinicians because, frankly, many suffer some degree of alexithymia and struggle to identify their own emotional states. If that’s the case, then it will be strange and difficult to speak from the heart. It might be easier to at least start on the cognitive level: you need to really believe what you’re saying. Despite what it sometimes feels like, your patient isn’t on a conveyor belt, and you speaking with them is an opportunity for genuine human interaction.

Know why you’re telling this story. A lot of medicine is very technical. We intervene to raise or lower blood pressure, stent lumens, and protect organs. The difference between a compassionate clinician and a quack or charlatan is that the compassionate clinician attempts to use interventions that have evidence for effectiveness. But all that technique needs a context. We don’t raise or lower blood pressure for it’s own sake, but for the good of the person and their health. There is, as Pellegrino argued, a hierarchy of goods, with the bare medical good only one, indeed the lowest, among them. The others, in order so that each serves those that come after, patient’s perception of the good, the human good (e.g., human rights), and the spiritual good. That last one isn’t necessarily religious, and its more relevant name might be the “narrative good,” for its the transcendent meaning of the person’s life. If one intervenes at the level of the medical good while ignoring or even harming the others, then you can’t say you’re doing good medicine. While Pellegrino’s hierarchy isn’t perfect (why this order, after all?), it does provide some handles for thinking about where we’re aiming when we use our chemicals and plastic to help someone who’s sick. Ultimately, we’re helping patients to tell stories that will preserve and restore health, whatever bit of it they might have left.

Some might balk at the importance of narrative in the experience of illness. For clinicians, I hope what I’ve written so far makes the case that your co-authorship in a patient’s story is inevitable and often indelible. You have a choice about what kind of co-author you’ll be.

For patients, perhaps you’re like Brian Teare who, when faced with an onslaught of alarming symptoms, was shunted toward the health department due to lack of other affordable options. His experience showed him that illness isn’t one of narrative. “…my becoming ill was never a call to story,” he explains, “It was a call to restore my bodily equilibrium.” He voiced his frustration that the city clinic’s limitations were “the result of many powerful systems colluding to render my body chaotic and voiceless.” Teare refused to believe what Broyard had written years before: “Always in emergencies we invent narratives,” but even Teare couldn’t escape trying to bind his illness with words. We do have his reflection in the Boston Review after all. Some things exceed or eradicate language, like pain, but that doesn’t stop us from trying to talk about them.

The bodily experience of illness is chaotic and numerous forces, like the privately certain but publicly doubted symptoms, the isolation, the fatigue, and so on, militate against its comprehension and telling. The person who can tell their clinician a coherent story of what’s going on is often at an advantage over someone who struggles to begin such a story. But that doesn’t make them a “poor historian.” They may seek mere “bodily equilibrium” like Brian Teare, but not for its own sake. They want it so they can return to their lives, to enter again into their own stories. Sometimes they can, but often, particularly in serious and chronic illnesses, that story is different. “Bodily equilibrium” looks different. How the pieces fit together depend on how patients, families, and clinicians tell the story.

What kind of story can we tell today about health?

Trajectories

Following a meandering reading-path, sharing some brief commentary along the way.

“Who are we caring for in the ICU?”

Daniela Lamas, an ICU doctor, writes of her experience in working to keep someone alive at the behest of their family. Not because the patient necessarily wanted this nor because they thought it was best for the patient, but because this is what the family wanted for a time. What does it mean to care for the family and not just the individual patient amidst critical illness? Is that even possible? Tensions like these almost always remind me of Wendell Berry’s short story “Fidelity,” cited above, about the death of Burley Coulter, one of the pillar characters in Berry’s fictional town of Port William, Kentucky. It reminds me that people belong to their families, not to the hospital. Of course there are limits (neglect and abuse come to mind), but one of my tasks as a clinician is to restore patients to community however I can. Sometimes that mean continuing life-sustaining therapy for a period of time as these people try to make the best decisions possible for their critically ill loved one.

“Moral formation is not a technical project”

This conversation between Benjamin Long and Warren Kinghorn focuses on the moral formation of medical trainees. This issue rose to the fore in the early 2000s under the guise of “professionalism.” Kinghorn puts his finger on the reason why this continues to bedevil medical educators by highlighting Aristotle’s differentiation between “techne” and “phronesis.” Techne, as Kinghorn explains, is the application of reason in designing a process that produces a product. Taking a student who knows nothing about hyponatremia and teaching them how to diagnose and manage hyponatremia is an example of a technical educational project. Phronesis, on the other hand, is practical wisdom, which allows us “to guide human action in a particular way, a way in conformity with excellence consistent with eudaimonia,” that is, flourishing. To believe we can produce virtuous clinicians by means of a technical process is a category error. Long and Kinghorn discuss how one might instead grow in virtue. Spoiler: because it’s not technical, it’s highly relational, idiosyncratic, and likely inefficient. That’s not bad, but it won’t satisfy technical markers of progress and production.

“The platinum rule: a new standard for person-centered care”

Harvey Chochinov argues that we should modify the golden rule (“do unto others what you would want done unto yourself”) into the platinum rule (“do unto others the way they would want done unto themselves”). This is easier said than done, though, as patients are so often ambivalent (as cataloged in this very helpful review by Bryanna Moore et al). “Getting to know patients,” for example, as short-hand for helping them make complicated medical decisions belies the complicated process of literally helping them construct their choices. It’s not like those decisions are latent inside the patient, awaiting discovery by a neutral clinician. I appreciate Chochinov’s offer of a de-biasing tool, for we shouldn’t ride rough-shod over someone, and still it’s limited and can actually exacerbate the difficulties in medical decision-making.

“Caught in a loop with advance care planning and advance directives”

The field of palliative care, at least in the USA, is struggling to know what to do with recurrently null or unrevealing outcomes in research on advance care planning (of which the creation of advance directives is a part). Advance care planning and serious illness communication, to the extent that we wish to study them, may be wicked problems. Contexts can be so different with so many different inputs and competing perspectives that we probably won’t find the way to conduct these conversations or help people make sound medical decisions. This conversation in Journal of Palliative Medicine helps shed light on how thoughtful people who have been in the field for a while are seeing the issue now and where they hope to move forward.

“Stability of do-not-resuscitate orders in hospitalized adults”

“Confirming code status” has become a routine feature of most clinicians’ admission H&P. Even for those who have clearly documented goals and preferences, some clinicians believe it’s important to confirm a patient’s code status for themselves at admission and with transfers in care. This, they believe, is ultimately in deference to the patient’s autonomy. This helpful study shows that code status reversals are associated with where the patient is currently receiving care - e.g., a hospital that culturally provides a low rate of DNAR orders. Perhaps some of this is related to an actual change in preferences, but the fact that things like admission location has such a prominent influence either suggests the original order was not aligned with the patient’s goals, or their reversal isn’t actually aligned with their goals. Either way, we see that decisions about code status (like many other preferences about medical care) are highly context dependent and can be influenced by any number of factors. Knowing this is the case, what is our job as clinicians?

“The time toxicity in cancer treatment”

For patients pursuing cancer-directed therapy, their lives often end up scheduled around infusion sessions, pharmacy lines, and doctors’ visits. These authors helpful draw out the “time toxicity” of that regimen, that is, the time spent away from home and doing activities that are meaningful to the patient. This is a helpful concept, particularly in helping clinicians understand just how burdensome some of their regimens might be. However, we also need to discern how burdensome patients find these things. Anecdotally, I’ve found that some don’t want to spend any time in their remaining months in a waiting room, while others aren’t particularly bothered by it if it means they might have a few more weeks. Just like a physiologic toxicity, time toxicity is likely individual.

“Biased Evaluation in Cancer Drug Trials-How Use of Progression-Free Survival as the Primary End Point Can Mislead”

Understanding the role of surrogate endpoints is critical to, well, critical trial appraisal. The endpoints that matter most to patients impact things like survival, function, and symptoms. Other things that matter that are rarely endpoints in clinical trials are things like financial toxicity and time toxicity. “Progression-free survival” has a unique place in oncology trials. Whether it correlates with overall survival or symptom improvement depends on the type of cancer and the agent under investigation; you can’t extrapolate from one context to another. Clinicians should keep this in mind as leap from medical evidence in an attempt to generalize results to the specific patient for whom they’re caring.

More evidence, albeit retrospective, showing that families should be at the bedside of patients in the ICU if at all possible. There are some family-centered factors that prevent this (e.g., geography, transportation), but hospital policies (e.g., COVID visitor restriction) should not be a barrier. Whatever a hospital does to get a clinician to the bedside they can do to get a family member to do the bedside.

Closing Thoughts

“Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly now. Love mercy now. Walk humbly now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.”

Pirkei Avot