Notes from a Family Meeting is a newsletter where I hope to join the curious conversations that hang about the intersections of health and the human condition. Poems and medical journals alike will join us in our explorations.

For those of you just joining, consider starting here to trace how I’ve been thinking about medicine and technology, a conversation I’ve been returning to time and again.

Quintin pushes away his breakfast tray. His twin daughters urge him to eat something, anything. He shakes his head. His wife, as frail as he is, watches, her brow furrowed. She knows him too well to argue when he’s got that stubborn look.

His daughters step out for lunch. Appreciating that her husband is under the watchful eye of his nurse, his wife, too, steps away to use the restroom. A physician slips in and after three minutes, leaves.

“Does he have capacity?” The physician later asks the hospitalist caring for Quintin. The hospitalist admits they hadn’t considered it. They thought so, maybe.

This question hangs over contentious, high stakes medical decisions. It haunts clinicians who care for people who are seriously ill. Framed like this, it presupposes the capacity to make a medical decision either encompasses all medical decisions, or else the listener knows what decision is referenced. If the patient “has capacity,” then the patient decides. If not, then the quest to identify and talk with the surrogate begins.

Sometimes - often, actually - this patient has the capacity to make this particular contentious, high stakes medical decision, but just barely.1 Or maybe they’re frequently delirious, but today they’re not. Or maybe the clinician feels they fall solidly within the bounds of “capacity” and so the clinician proceeds with a high stakes conversation with the unaccompanied patient.

What a clinician’s behavior suggests in each of these cases is a belief that these patients can proceed with a major medical decision alone. After all, the criteria for decision-making capacity are all located within the individual decision-maker: they must understand the relevant information, appreciate its relevance to their situation, reason about the options, and communicate a choice. It’s one thing to assess these (important!) abilities, however, and another to treat a patient as if they are a will making decisions about a body that is only accidentally their own.

Is Quintin more than his capacity to make decisions? I’m sure any clinician would immediately affirm this. But that’s not how patients like Quintin are seen and treated. Why?

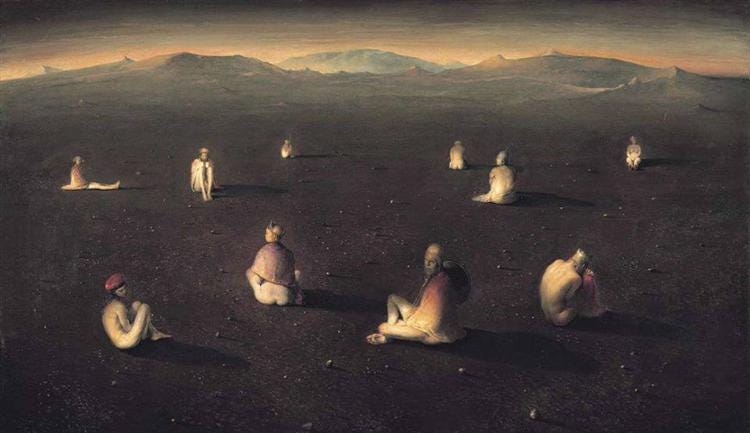

Look At All the Lonely People

Most modern Western societies face a challenge: how do you administer justice across a population with diverse beliefs about goods, ends, purposes, and meaning? Michael Sandel observes that a liberal vision of a just society

“…seeks not to promote any particular ends, but enables its citizens to pursue their own ends, consistent with similar liberty for all; it therefore must govern by principles that do not presuppose any particular conception of the good. What justifies these regulative principles above all is not that they maximize general welfare, or cultivate virtue, or otherwise promote the good, but rather that they conform to the concept of right, a moral category given prior to the good, and independent of it.”

The political philosopher John Rawls attempted to tackle this problem. He imagined a state in which people totally unfettered by real world commitments, ties, burdens, relationships, or duties would make decisions about procedures of justice. They wouldn’t know how things would shake out for them after they cross over into the real world: will they be rich or poor? White or black? Sick or well? From behind this “veil of ignorance” these people would decide the rules of justice and they would do it equitably because they have nothing to bias them. They would develop procedures of justice that optimize individual liberty without presupposing anything about what goods should be pursued with that liberty.

This is, of course, a hypothetical exercise. As far as we know, no one consulted with us before we were thrown into lives freighted with contingency. Rawls offers this as a tool to help people who are living in the real world think through matters of justice, maybe to arrive at some consensus that overlaps their varied beliefs. Someone pondering principles, rules, or laws might start “behind the veil,” then bring that policy out to be negotiated in the real world, return “behind the veil,” and so on. Through this process of reflective equilibrium they might eventually arrive at something just.

Although this person behind the veil is hypothetical, it presupposes something about real people. Michael Sandel argues this is the portrait of the “unencumbered self”:

“No commitment could grip me so deeply that I could not understand myself without it. No transformation of life purposes and plans could be so unsettling as to disrupt the contours of my identity. No project could be so essential that turning away from it would call into question the person I am. Given my independence from the values I have, I can always stand apart from them; my public identity as a moral person 'is not affected by changes over time' in my conception of the good.”

In order for the exercise to work, the person behind the veil of ignorance must be unencumbered by these identity-binding commitments. There is, as Sandel argues, always a difference between values I have and who I am.2 And it turns out, in the liberal conception of identity framed by Rawls, “who I am” is constituted only by self-chosen values and ends. Before we ever become “baker,” “mother,” “son,” or “senator,” we are distinct selves without any connections at all. Our capacity to choose is more fundamental to who we are than anything we could choose.3

We are ideally, essentially choosers free of the burdens of duty, relationship, or anything that might impinge upon our liberty. Justice should exist to optimize our liberty and approximate that ideal state so we’re as free as possible to choose whatever ends we like.

Respect for Autonomy

This cashes out in medical decision-making through the principle of “respect for autonomy.” Consider this from The Principles of Biomedical Ethics:

“…the principle should be analyzed as containing both a negative obligation and a positive obligation. As a negative obligation, the principle requires that autonomous actions not be subjected to controlling constraints by others. As a positive obligation, the principle requires both respectful disclosures of information and other actions that foster autonomous decision making. … the moral demand that we treat others as ends requires that we assist them achieving their ends and foster their capacities as agents, not merely that we avoid treating them solely as means to our ends.”

This principle, as articulated by Tom Beauchamp and James Childress, presumes the liberal anthropology outlined above. Clinicians cannot make any judgments about the ends of medicine but leave that to their patients. They have a duty (“moral demand”) to use their expertise to help patients pursue the ends the patients themselves have chosen. Because nowhere in Principles of Biomedical Ethics (as far as I’ve found) do Beauchamp and Childress tell us what healthcare is actually for, their entire project seems to presume this anthropology. We get a clearer idea this is the case in reading these words from Beauchamp about assisted suicide as the triumph of autonomy:

“Many in bioethics seem now to be coming to the acceptance of two important conclusions. First, they would like to see the law preserve a range of options for patients, including last-resort remedies such as refusal of nutrition and hydration and ingestion of a fatal medication. This is the logical extension of a primary commitment to patient autonomy. Second, many are coming to the view that physicians who provide assistance in hastening death are adhering to a legitimate interpretation of the physician’s traditional commitment to the patient: to care for and meet the needs and preferences of the patient in all stages of the patient’s life. They note that the activities a physician undertakes in providing assistance in hastening death are the same as those carried out by a physician who oversees a withdrawal of treatment.”4

You might say respect for autonomy is just one principle among four. Indeed, Beauchamp and Childress routinely claimed one principle cannot, de facto, trump the others. They must be weighed, balanced, and brought into a reflective equilibrium (borrowed from Rawls) to bear on any given dilemma. However, the anthropology I’ve described informs the other principles, lifting respect for autonomy to at least the first among equals. In practice, it seems it becomes their ruler.

Take nonmaleficence. Beauchamp and Childress admit that clinicians may harm patients, but it must be justified harm to avoid being a wrong. The example they provide is amputating the leg of a consenting person. Amputating a leg is a harm, but weighed against death and taking into account the patient’s consent, it doesn’t wrong the person. Most people readily agree on what constitutes harm, but when it comes down to something contested, it’s ultimately up to the patient to decide what’s wrong. Elsewhere, Beauchamp draws out this point by conflating the withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining therapies and intending a patient’s death, the details of which I started to explore previously:

“…if a person chooses death and sees that event as a personal benefit, rather

than a setback or deprivation of opportunities, then killing at the person’s request involves no clear harm or wrong. If letting die based on valid refusals does not harm

or wrong persons or violate their rights, how can assisted suicide or voluntary active euthanasia harm or wrong a person who dies? In each case, persons seek what for them is the best means to the end of quitting life. Their judgment is that lingering in life is worse than death. The person in search of assisted suicide, the person who seeks active euthanasia, and the person who forgoes life-sustaining technology to end life may be identically situated. They simply select different means to end their lives.”

In this framing, to develop the logic further, this patient isn’t just harmed but wronged by a clinician’s refusal to end their life. Why is that the case? Because medicine isn’t about healthcare; it’s about helping people advance the ends they deem most appropriate for their lives. The political anthropology that informs such a practice is to presume individuals are, at root, mere choosers. Medicine becomes a political instrument for pursuing liberty.

So US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg can argue that “…legal challenges to undue restrictions on abortion procedures do not seek to vindicate some generalized notion of privacy; rather, they center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.” Setting aside the debate about the morality of abortion itself, it seems to be a remarkable development that a society requires a medical procedure to ensure equality for all its citizens. But that is only because this intervention is but a subset of the broader expectation that medicine as a whole is intended to promote liberty.

The attempt to “keep politics out of medicine” is ironic and doomed fail. This is the case for two reasons. First, the clinical encounter is inherently political in the classical sense: it’s a negotiation on how to live well. Not only between clinician and patient, but between the field of medicine and society at large. The bounds of what the clinician can and should do for this person in the pursuit of living well are set by the ends of their practice of medicine but also the trust of society. Second, medicine as currently practiced is already deeply grounded in a liberal political anthropology. To claim that we should “keep politics out of medicine” is really a claim to leave the current political arrangement within medicine alone. The question isn’t whether medicine and politics can or should mix, but how they will mix, because mix they will.

This can get squirrely because health and liberty go hand-in-hand. We experience the goods of life through our bodies. Health (or the lack thereof) influences that experience. This is why the techniques of medicine are easily co-opted for political projects, subtle or obvious. Medicine offers power to bring political ideologies to realization within our bodies. The only basis on which clinicians could resist this co-opting is by appealing to a standard for their profession(s) that is separate from (even if related to) matters of liberty and justice.

Brains and Bodies

This liberal anthropology impacts more than medical decision-making. It frames how clinicians see their patients. If the person is essentially a chooser, and all their values and ends are self-chosen, then the body is at the will’s disposal. It’s just another possession. To even remain in the body, as Beauchamp suggests, is a choice.

Jeffrey Bishop believes medicine doesn’t really study life, not in its most robust sense anyway. Most medical students’ first professional exposure to the human body, the cadaver, represents how medicine views all bodies: dead matter. It’s ultimately up to the patient to imbue this meaningless matter with any sort of meaning. Bishop writes:

“The power of technology renders the practitioner forgetful of meaning and purpose. For medicine, then, the important question becomes, Who holds the power over physiological functioning? This question is an ethical question. The debate in medicine has not been about philosophically exploring ways in which life as such might be meaningful; instead, its focus has been on who can invest meaning back into, and who should exert power over, the meaningless mechanism, and on how to carry it out.”

Now, this isn’t how people experience their bodies. When we’re well, we “have a tacit sense of bodily certainty, and trust our bodies and their familiar performance,” as Havi Carel notes. However, illness dislocates us. Carel continues, “In illness, the body becomes an obstacle and a threat, instead of my home, a place I inhabit and whose ways are predictable. A change to one’s body is a change to one’s being-in-the-world.” Even without the aid of a clinician, illness make the body an object. But the clinical context, rather than assuaging this by bringing coherence, exacerbates the dilemma: “The body as object takes precedence in the clinical context, and its foreignness is accentuated by the patient’s inability to access some medical facts other than via a third person report.”

The clinical gaze, as Bishop calls it adopting Michel Foucault’s wording, does nothing to help re-integrate the ill person. People might be cured but not finally healed. Joel Shuman laments, “The specialist whose attention focuses on a particular aspect of the patient’s body—an aspect about which she knows a great deal and over which she may have a great deal of control—may nonetheless be able to do little to heal the patient simply because she is unable to ‘see’ the patient who needs healing.”

After all, it’s not up to clinicians to tamper with how people wring meaning out of their bodies. The important work for clinician to do is provide information for an informed decision and abide by the patient’s choice, using their technical expertise to act on the body in the way the person so desires. This perspective of the human body fits hand in glove with the liberal anthropology adopted by Beauchamp and Childress.

A Humane Anthropology

Two questions are worth addressing at this point. First, does it matter if this anthropology just described accords with reality? Second, does it actually accord with reality?

Remembering the dilemmas with which I opened this essay, our understanding of what a person is informs how we treat them, what we expect from them, what claims they can make on us, among other things. “Seeing a body,” Shuman observes, “is a decidedly different activity than studying it anatomically.” The endless concern over decision-making capacity is but a variety of procedural adherence to the standards of informed consent. Informed consent is a really important thing, and therefore having the capacity to make a medical decision is also a really important thing. But let’s not confuse two things: trying to discern whether a decision is autonomous, and understanding the person as autonomous. I have nothing to say against the former labor. However, the latter approach is that which concerns me here.

When we allow this liberal anthropology to leak into the clinical encounter, a few things get short-circuited:

We begin to see people as atomized individuals, rather than existing in a web of relationships, some of which are constitutive of their identity.

We blur, bend, or break medicine’s pursuit of health as the end of our practice for individual patients. Instead, it’s supplanted by the patient’s own ends, whatever they are (sometimes that may accord with health, sometimes not).

With that blurred, bent, or broken pursuit, we leave medicine vulnerable to administration by political (e.g., history of eugenics) or technocratic (e.g., enhancement) projects.

Thus, it matters a great deal whether our anthropology accurately describes the person under our care.

It seems this liberal anthropology does a very poor job of describing what humans actually are, which means it serves very poorly to help us see our patients well. Carter Snead shares this concern when he reviews various aspects of American law as it relates to bioethical issues. What the law forgets (and I add, what clinicians forget) is that we are embodied beings:

“American law and policy concerning bioethical matters are currently animated by a vision of the person as atomized, solitary, and defined essentially by his capacity to formulate and pursue future plans of his own invention. The "natural" world and even the human body are, by contrast, understood as merely inchoate matter to be harnessed and remade in service of such projects of the will.”

This just isn’t what humans are. Instead, “…because human beings live and negotiate the world as bodies, they are necessarily subject to vulnerability, dependence, and finitude common to all living embodied beings, with all of the attendant challenges and gifts that follow.” Insofar as law (and medicine) are meant to help people flourish, as Snead argues, its practices will fall short when it misperceives the human person.

It is true that medicine involves making decisions. It’s also true that a big part of being a good clinician involves helping your patients make those decisions and using our expertise to manipulate the body. But an overly procedural, technical focus on decision-making can trick clinicians into believing patients (or their surrogates) are mere rational wills that will spit out a decision upon receipt of the relevant information. It also overlooks the deeply existential nature of many medical decisions: this isn’t just about my body, this is about me. But clinicians miss that because the body has become mere matter to be kept moving.

This shift in outlook has big consequences. Alasdair MacIntyre has this to say:

“The history of any self making this transition [into maturity] is of course not only a history of that particular self, but also a history of those particular others whose presence or absence, intervention or lack of intervention, are of crucial importance in determining how far the transition is successfully completed. And those others enter into that history in two different ways. They provide first of all the resources for making the transition, by nursing, feeding, clothing, nurturing, teaching, restraining, and advising. What resources an individual needs varies with circumstances, temperament, and above all the obstacles and difficulties that have to be confronted. We need others to help us avoid encountering and falling victim to disabling conditions, but when, often inescapably, we do fall victim, either temporarily or permanently, to such conditions as those of blindness, deafness, crippling injury, debilitating disease, or psychological disorder, we need others to sustain us, to help us in obtaining needed, often scarce, resources, to help us discover what new ways forward there may be, and to stand in our place from time to time, doing on our behalf what we cannot do for ourselves. Different individuals, disabled in different ways and degrees, can have their own peculiar talents and possibilities, and their own difficulties. Each therefore needs others to take note of her or his particular condition.”

What this should inspire, MacIntyre argues, is the cultivation of “virtues of uncalculated giving and graceful receiving.” I don’t want to go too deeply into what those are right now. I mention them because human society as a whole and human development individually require these virtues. As Snead poignantly observes, “If we remember that our embodiment renders us vulnerable and dependent upon the beneficence of others for our very lives and self-understanding, we will more clearly grasp our obligations of just generosity and reciprocal indebtedness to those others who are likewise vulnerable...”

Even if we wanted to (which we shouldn’t), we can’t dispense with everyone who demonstrates some degree of vulnerability, dependence, or limitation because that includes all of us. We all begin, move through, and end up in states of vulnerability, dependence, and limitation. But the only way to see the value in these virtues and cultivate them is to see the human person for who they really are. The liberal anthropology described by Rawls and embedded in the most popular approach to biomedical ethics just doesn’t do the work we need it to. It leaves clinicians demoralized and patients dehumanized.5

What about Quintin? I wonder if seeing him differently could shape even how we think about the assessment of his decision-making capacity. Rather than triyng to expeditiously procure a decision, we appreciate Quintin’s embeddedness within the web of relationships that make him who he is. While it is true and important that Quintin will need to demonstrate certain abilities to authorize an important medical decision, those abilities might best be accessed with the support of his family. The assessment itself might not be a purely technical endeavor, either, but it could be undertaken with the gravity of someone who appreciates that what we’re discussing isn’t only what’s going to happen to Quintin’s body, but what’s going to happen to Quintin himself.

In a short story by Wendell Berry, an old farmer named Burley Coulter has fallen ill. His family, worried about him, takes him to his doctor, who sends him to the local hospital. Soon, he’s transferred to the big city hospital. This may sound familiar to any clinician who has worked in any of these roles: a very sick patient being passed up the chain into ever-more complex care settings. Now, here he is:

“Burley remained attached to the devices of breathing and feeding and voiding, and he did not wake up. The doctor stood before them again, explaining confidently and with many large words, that Mr. Coulter soon would be well, that there were yet other measures that could be taken, that they should not give up hope, that there were places well-equipped to care for patients in Mr. Coulter’s condition, that they should not worry. And he said that if he and his colleagues could not help Mr. Coulter, that they could at least make him comfortable. He spoke fluently from within the bright orderly enclosure of his explanation, like a man in a glass booth. And Nathan and Hannah, Danny and Lyda stood looking in at him from the larger, looser, darker order of their merely human love.”

These are two ways of seeing. I don’t think I need to see my patients as family but I could see them as the people they are.

“Just barely” is, I admit, a subjective assessment, more of an intuition than a standard. Most clinicians have probably met someone who can parrot back the burdens and benefits of an intervention and weigh the various options in a rudimentary way. They check the formal boxes but still there remains a niggling doubt this person may not appreciate the full depth of their decision.

Interestingly, and a direction I could go another time, this also seems to orient some forms of psychotherapy, like acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Clients focus on “values authorship” and recognize they need to “de-fuse” from thoughts, beliefs, and emotions that inhibit the pursuit of valued living and psychological flexibility. There is a perceiver behind all these values, and some of the mindfulness exercises in ACT presume just that. This very well could be a therapeutic deployment of Rawls’ political philosophy.

You may wonder why, if these selves are empty of values roles behind the veil of ignorance, we need multiple people back there anyway? Sandel asks this same question. These people aren’t just similarly situated; they’re identically situated, and agreement doesn’t mean much of anything. It provides an appearance of democracy but it’s really just rule by a single, blank brain.

It also fuels the quest for robotic companions: something that can shore up our vulnerability without requiring us to bare ourselves to another person.