Notes from a Family Meeting is a newsletter where I hope to join the curious conversations that hang about the intersections of health and the human condition. Poems and medical journals alike will join us in our explorations.

For those of you just joining, consider starting here to trace how I’ve been thinking about medicine and technology, a conversation I’ve been returning to time and again.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past. All of us labor in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.”

William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

Eunice is confused. She cared for a patient last week who received what seemed like the red carpet treatment, but this week a patient with the same condition is getting short shrift. What’s going on?

Ian and Lisa don’t see eye-to-eye on Mr. Randolph’s treatment plan. In fact, they’re no longer on speaking terms, which makes caring for their mutual patient very challenging. How can they work together to provide the best care possible?

Jermaine suspects that Ms. Townsend, if she had the capacity to make this medical decision, would make one choice, but her sister (and surrogate decision-maker) is choosing differently. The physicians appear to merely acquiesce which seems wrong. Jermaine feels frustrated and torn. What should he do?

Enter clinical ethics consultation (CEC).

The American Society of Bioethics and Humanities (ASBH) defines CEC as “a set of services provided by an individual or group in response to questions from patients, families, surrogates, healthcare professionals, or other involved parties who seek to resolve uncertainty or conflict regarding value-laden concerns that emerge in healthcare.”

Healthcare abounds with quandaries and conflicts. These arise from the diversity of people who encounter one another. Not everyone believes the same thing, or if they do, they may not reach the same conclusion on how to apply it. Quandaries and conflicts also bubble up from the ambivalent nature of technology, which may pull for uses that shake and confuse our standard practices and worldviews. Suffering and illness foment some of the deepest quandaries and conflicts too, as everyone involved grapples with the existential elements of the human condition. CEC exists to help Eunice, Ian, Lisa, and Jermaine; even more so, CEC exists to help their patients.

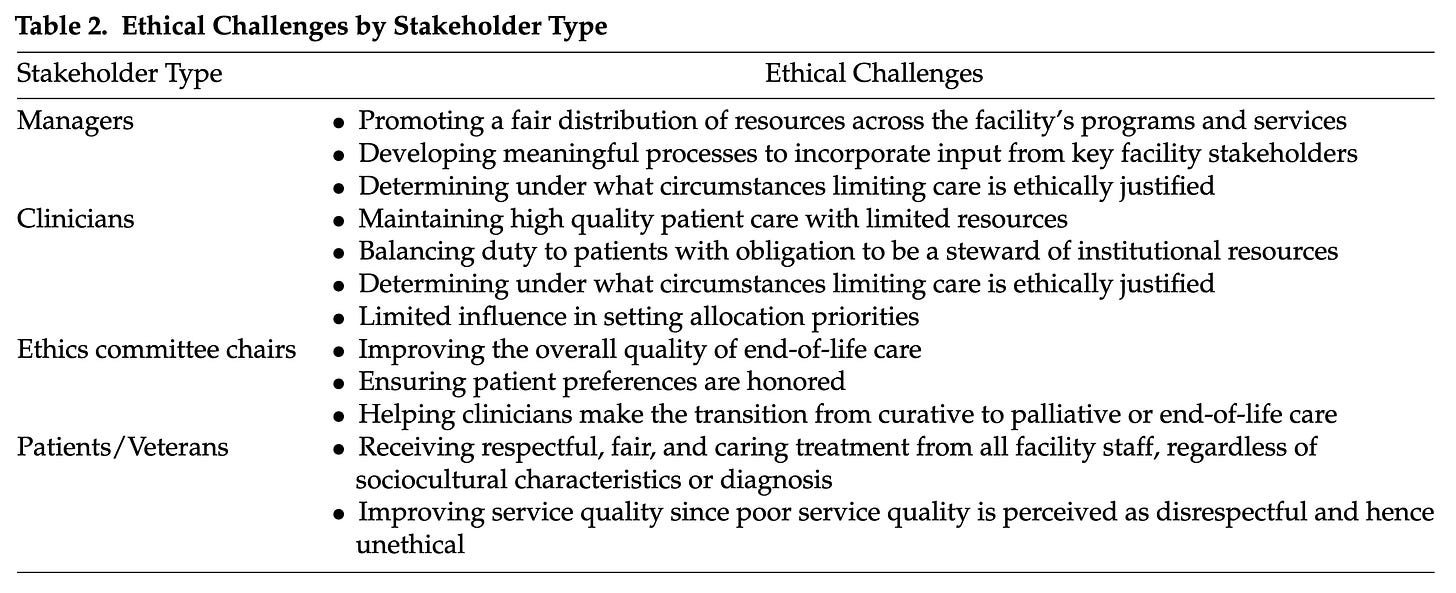

But who gets to determine what quandaries and conflicts are addressed by CEC? One study interviewed various people in Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals and found these perspectives:

CECs address most of these things - until you get to the concerns of patients. How can a CEC help patients “receive respectful, fair, and caring treatment from all facility staff?” How can a CEC help improve service quality? In most healthcare systems, issues around quality are usually routed elsewhere (e.g., HR, quality improvement). Most clinicians don’t view care quality as an ethical problem, per se, unless they discover someone doing something wasteful or careless.1 Of course unethical care is probably going to result in disrespectful, unfair, uncaring, poor quality care, but a healthcare system has other mechanisms for handling these apart from CEC, even if a CEC might have something (interesting?) to say about it.

Nevertheless, I think patients see something here: healthcare is an intrinsically moral practice. You don’t have ethics over here and medicine over there. This will shape how we think of ethics education and moral formation across healthcare. It seems to reach beyond how ASBH understands the primary work of the CEC.

Okay, but at least among those things we agree fall squarely within the purview of CECs, can we expect consistency in how those quandaries and conflicts are addressed?

Probably not.

A recent study found that bioethicists’ views vary quite a bit on a number of controversial issues (although with a notably progressive slant):2

People think it’s feisty when folks from the dark green and red go toe-to-toe, but there’s a lot of heat amidst the light green and yellow too. How lines get drawn around something “generally” or “not generally” ethically permissible might hinge on a single criterion, distinction, or definition. People wrestle one another to the ground over small but critical details.

From this, I see two challenges facing CEC: a diversity of perspectives among stakeholders in what constitutes “ethics,” and a diversity of beliefs about controversial issues that might resist standardization across consultants, health systems, and the field. Are these bad things?

To tackle that question, let’s start by taking a peek at ASBH’s standards for CEC.3

ASBH recommends the “ethics facilitation approach” to the quandaries and conflicts that populate the land of medicine. In this approach, one uses a set of skills to do things like “identify, clarify, and analyze specific ethical questions, concerns, dilemmas, or conflicts pertinent to the given situation,” “facilitate mutual understanding of relevant facts, values, and preferences,” and “support ethically appropriate decision-making while respecting differing points of view, values, cultures, religions, and moral commitments of those involved.”

Ultimately,

“by encouraging and modeling open, inquisitive communication, the ethics facilitation approach helps involved parties identify and elucidate their values and moral commitments, including previously unarticulated values, so that they can be discussed openly and respectfully to generate creative and well-considered decisions. In addition, the healthcare ethics consultants’ knowledge of ethical theory may help to name and frame the values underlying the different perspectives of those involved. Such naming and framing can often lead to a deeper understanding of, and respect for, those perspectives and values, which can facilitate the development of an ethically justifiable plan of care.”

This is important work because sometimes conflicts arise from miscommunication, competing values, or a failure to appreciate our own and others’ presuppositions. This aspect of CEC doesn’t involve passing down a moral law from upon high, but rather being sensitive to how people think about the things that matter most to them. CEC is often like negotiation, helping participants to reach a creative, mutually agreeable path forward.

Still, consultants require a substantial cache of knowledge to navigate these quandaries and conflicts, ranging from familiarity with consequentialism and virtue ethics all the way to feminist ethics and institutional policy. How a consultant sorts out, within themselves, their own commitments in relation to their knowledge of these areas is something ASBH leaves unstated.

ASBH also recommends all members of an ethics consultation team have virtues like integrity, compassion, courage, honesty, humility, prudence, curiosity, tolerance, patience, and trustworthiness. “Programs that educate and train healthcare ethics consultants should help learners develop these attributes, attitudes, and behaviors.” ASBH doesn’t spell out what this actually means. While Improving Competencies in Clinical Ethics Consultation: An Education Guide summarizes skills and knowledge for the consultant to possess, it doesn’t address at all these characteristics it finds so important. What does it look like to help learners develop these things? ASBH leaves that unanswered.

If I can try to summarize what the ASBH expects of clinical ethics consultants, I might say consultants must possess knowledge, skills, and characteristics necessary to address ethical quandaries and conflicts that arise in medicine. All of this can be taught without reference to a particular moral tradition.

Who am I to take issue with what ASBH claims are the core competencies of ethics consultation? I’m just someone who wants to join the conversation about what we do when we talk about ethics in medicine. So, read the following two concerns with whatever skepticism you feel is warranted.

Missing Tradition

ASBH explicitly recommends characteristics (i.e., virtues) that ethics consultants should possess. However, it seems to assume that the content of these virtues is shared and intelligible across medicine. I worry this isn’t necessarily the case, not only because it allows people to fill up the virtue-words with idiosyncratic content, but because it lacks the moral fabric, in the form of a community, to sustain those virtues - beyond merely requiring them for certification. A tollbooth operator can define words however they wish and demand acquiescence from people who want to cross their bridge. That doesn’t mean those definitions will have any enduring potency.

Warren Kinghorn and colleagues warn those who think we can glean virtues from moral traditions and ignore the traditions themselves:

“The professional virtues, like spring flowers, bloom and grow most fruitfully in the context of the particular, specific grounding traditions that originated and sustained them. Cut off from these traditions, they begin to fade and wither, to become increasingly arbitrary, anemic, and perfunctory. But explicit acknowledgment of these traditions in a pluralistic culture entails the risk of moral disagreement and division.”4

It’s not enough to learn to be “compassionate,” if compassion is understood as a skeletal characteristic isolated from a community that sustains it and a tradition that shapes it. Compassion of that kind becomes a lever for an agenda that might be antithetical to the telos of medicine. Compassion instead becomes a word used to squeeze efficiency out of beleaguered clinicians.5 The alternative would be to bring into conversation people of traditions that imagine and see compassion differently, people who belong to these traditions rather than trying to design a one-size-fits-all Diet Compassion.

This aligns with Alasdair MacIntyre’s observation that, while our own culture is quite different from the so-called “heroic traditions” of the ancient world, we can still learn something from them:

“If the heroic virtues require for their exercise the presence of a kind of social structure which is now irrevocably lost - as they do - what relevance can they possess for us? Nobody now can be a Hector or a Gisli. The answer is that perhaps what we have to learn from heroic societies is twofold: first that all morality is always to some degree tied to the socially local and particular and that the aspirations of the morality of modernity to a universality freed from all particularity is an illusion; and secondly that there is no way to possess the virtues except as part of a tradition in which we inherit them and our understanding of them from a series of predecessors in which series heroic societies hold first place.”

We cannot get around the fact that we all belong to stories. There is no vantage point where we can shed our commitments and speak “objectively.”

Margaret Walker agrees:

“One recurrent theme is the social situation of morality: moral understandings are always embedded in and make sense of a particular social setting and its characteristic relationships, problems, and practices. This warns us off trying to abstract some pure all-purpose core of moral intelligence from the historically specific assumptions and circumstances that give moral conceptions their point and meaning.”

So, too, Arthur Frank:

“How people can imagine acting in the present—what counts as right or good—is generally a continuation of earlier stories. The present is a sequel that follows the narrative logic of earlier episodes. People can and do act differently than what past actions predict; they go against the grain. But most people’s default setting is continuity with past stories. Even when there is a break in continuity, the past story remains crucial for understanding what is being broken away from.”

Paul Wadell writes more firmly still:

“We cannot separate quandaries from the persons who confront them, for we do not stand before problems as neutral spectators, but as people whose point of view is entailed by our convictions and beliefs, people whose very way of life, whose moral history, leads us to see situations a certain way. There is then an indissoluble connection between the problems we face and the people we are, a connection so tight, [Stanley] Hauerwas suggests, that to change our minds about a moral question is also to change ourselves.”

I am not at all suggesting that truth, even moral truth, is relative. I don’t think any of these authors would suggest as much either. I believe some things are wrong, period, and some stories are so damaged or so twisted by evil as to make them antithetical to flourishing, although even those stories aren’t beyond redemption.

I'm also not suggesting my opinion is as good as theirs, or your opinion is as good as mine, or his opinion is as good as hers. Generally, people who have a deeper knowledge of themselves, the world, and their work may have an overall better opinion than someone less reflective.6

What I hope this brief survey supports is that we cannot access a vantage point from nowhere. There are only views from somewhere. When we try to get outside any tradition, what we do is make ourselves more vulnerable to self-deception. We trick ourselves into believing everyone else is embedded in a culture, tradition, or religion, but we ourselves aren’t, or if we are, we can use tools without reference to our tradition. If you’ve ever interacted with someone like this, you may have found them arrogant, frustrating, and, if they had power over you, demoralizing. An ethics consultant who behaves like this could corrode the morale and reflective capacity of the community to which they belong. Or they might earn a reputation as the “ethics police,” useful only when you need to lay down institutional law that binds clinicians in the most obvious of ways. No good.

Well, maybe we can just practice medicine and outsource the quandaries and conflicts to CEC, because the practice of medicine is “objective?”

MacIntyre elsewhere argues that when people compartmentalize their lives like this (medicine over here, ethics over there), they disintegrate their agency. They lose the capacity to judge the various roles they inhabit and the virtues necessary to direct their will toward a constant end:

“[This self] cannot have integrity, just because its allegiance to this or that set of standards is always temporary and context-bound. And it cannot have the constancy that is expressed in an unwavering directedness, since it recurrently changes direction, as it moves from sphere to sphere. Indeed its conception of a virtue will generally be one of excellence in role performance rather than of excellence as a human being and hence what is judged excellent in one role-governed context may be very different from and even sometimes incompatible with what is judged excellent in others.”

An excellent bureaucrat is one who has no integrity or constancy. They do whatever is needed for the sake of their role. Although bureaucracies want clinicians and ethicists like this, I don’t think real clinicians, patients, or (most?) ethicists want this. We want clinicians and ethicists with integrity and constancy, who speak and act from conviction toward a substantive telos of medicine. In order to do that, they need to own their convictions, including the contingency of those very convictions.

The sooner we realize CEC is in the same boat of historical contingency as natural law reasoning, virtue ethics, consequentialism, and all the rest, the sooner we can start to grapple with the possibility that there may be more to do than ponder quandaries and resolve conflicts.

Even ASBH is operating within a historically contingent frame. That isn’t bad. That’s just how it is, the same for any other individual or institution. The least we could do is be honest and open about it. That might actually be the beginning of the path toward doing the most we could do! What would it look like for ethics consultants to own their commitments and their work as border-walkers among the many traditions of the stakeholders in medicine? Much of what ASBH recommends would still apply, but with the possibility of a greater richness in conversations that occur at the borders between traditions. You might start to see case reports like this pop up in the literature: “A request for hastened death: a conflict between an humanist-atheist patient and a Hindu clinician, as mediated by an Orthodox Jewish ethics consultant.”

Okay, maybe not the most compelling title, but hopefully you catch the idea. Kinghorn and colleagues call this “…open pluralism: a commitment to explore, understand, and hear the voices of the particular moral communities that constitute our culture.”

In such an openly pluralistic frame of CEC, a consultant would need to reflect on their own commitments on a case-by-case basis. What’s obvious and taken-for-granted for them might be revelatory or anathema to someone else. A consultant would rely on their knowledge, skills, and virtues, but they wouldn’t try to hide the fact that they also inhabit a particular tradition that might offer something toward a creative resolution of the quandary or conflict. They themselves are a part of this particular health care community faced with this particular challenge after all. They need to live and work there too. They’re contributing to a particular culture, just like the others.

Which brings me to my second concern.

More than Quandaries and Conflicts

People only think of reaching out for help from an ethics consultant when there’s a challenging quandary or conflict. Of course. What else would an ethics consultant do?

This is the subtle education clinicians get throughout training and onward for the rest of their careers: ethics is what you do when something goes awry. Everything else - the time you spend prescribing amoxicillin, typing your assessments and plans, performing cholecystectomies, bantering with colleagues in the workroom, ordering daily labs - is just normal. This siloing of ethics into a land of quandaries and conflicts lulls us into believing that there aren’t other processes that shape how we come to see and even generate those quandaries and conflicts.

Consider this: ASBH argues the deepest question of CEC is, “Who shall decide?” This is the question that cuts through all other questions when a conflict becomes intractable. Maybe it’s the patient, maybe a family member, maybe a guardian, but someone will decide because the focus of all clinical quandaries and conflicts is the moment of decision. That is the main event.

However, what ASBH misses is something MacIntyre sniffs out:

“For in a society in which preferences, whether in the market or in politics or in private life, are assigned the place which they have in a liberal order, power lies with those who are able to determine what the alternatives are to be between which choices will be available. The consumer, the voter, and the individual in general are accorded the right of expressing their preferences for one or more out of the alternatives which they are offered, but the range of possible alternatives is controlled by an elite, and how they are presented is also so controlled. The ruling elites within liberalism are thus bound to value highly competence in the persuasive presentation of alternatives, that is, in the cosmetic arts.”

In MacIntyre’s view, the decision isn’t the main event, but the final, perhaps almost inevitable, step of a process. MacIntyre seems to agree with Iris Murdoch when she wrote:

“I can only choose within the world I can see … If we ignore the prior work of attention and notice only the emptiness of the moment of choice we are likely to identify freedom with the outward movement since there is nothing else to identify it with. But if we consider what the work of attention is like, how continuously it goes on, and how imperceptibly it builds up structures of value round about us, we shall not be surprised that at crucial moments of choice most of the business of choosing is already over. This does not imply that we are not free, certainly not. But it implies that the exercise of our freedom is a small piecemeal business which goes on all the time and not a grandiose leaping about unimpeded at important moments. The moral life, on this view, is something that goes on continually, not something that is switched off in between the occurrence of explicit moral choices. What happens in between such choices is indeed what is crucial.”

We fail to appreciate, then, how desiccated our perspective becomes if we merely defer to the individual to break a tie in an ethical conflict. They themselves are beholden to their own story, their own tradition, their own community. But we all are becoming more beholden to something else: the inexorable pull and promise of technology. Daniel Callahan worried about this:

“The greatest fear of liberal individualism is authoritarianism. But that fear, reasonable enough, fails to take account of the fact the power of technology, and the profit to be made from it, can control and manipulate us even more effectively than authoritarianism. Moral dictators can be seen and overthrown, but technological repression steals up on us, visible but with an innocent countenance, and is just about impossible to overthrow, even as we see it doing its work on us. Liberal individualism makes this scenario more easily possible, and that is why it is not a tolerable guide to the sensible use of medical knowledge and technology.”

To defer to the individual may, in some cases, mean deferring to the whispered promises of technology. Gríma Wormtongue is alive and well in medicine, and makes the kings and queens of medical decision-making weak. Technology has this power to shape, and sometimes cripple, decision-making.

So too do the choice architects of medicine - the frontline clinicians, hospital formularies, and insurance agencies who offer or don’t offer certain medical interventions, who construct the options among which the individual patient will choose. They can nudge a patient this way or that. Even before the moment of decision, though, a patient’s relationship with individual clinicians and a whole healthcare system will shape how and when they make decisions and what decisions they’ll make. One patient’s wife wouldn’t change her mind about the plan of care which, in other circumstances, she would have chosen for him. Why? Because she didn’t trust his team to carry out the plan she actually wanted. This is a conflict about a decision, to be sure, but it sparked from months of abrasion between this woman and people caring for her husband.

Most people will be familiar with social determinants of health (SDOH), like poverty and education. These too shape patients to become the kinds of people who, yes, make certain kinds of decisions. We can evaluate those circumstances are just or unjust, and work to ameliorate them - maybe for the sake of health, but also in a way that helps us situate health among other important goods in life.

None of this, I don’t think, is deterministic. I still believe people can have agency in such a world, although it can be very hard, particularly when you’re sick and suffering. This provides all the more reason for us to broaden the scope of our vision beyond the mere quandary or conflict.

We, as a society and as health care systems, would do well to move further upstream from the quandaries and conflicts to consider our (tradition-given, tradition-shaped) presuppositions. What do we make of the human person? What is health? What are the limits of medical intervention? What is goodness? How do we discern truth, and what is true?

What have we to fear by doing this in conversation with others who are different from us? I suppose that we ourselves might be changed. But we are already under that threat from technological innovation itself. We are already changing (decomposing, I suppose) if we fail to reflect on our commitments and how they relate to our work. We might try to hide in the ever more isolated tombs of some echo chamber, but the only comfort found there is the stillness of death.

Instead, if we step out into the light, we’re confronted with the dizzying diversity of a world that challenges our preconceived notions.

We face questions.

There is power in the question, as Neil Postman recognized:

“The form of a question may ease our way or pose obstacles. Or, when even slightly altered, it may generate antithetical answers, as in the case of the two priests who, being unsure if it was permissible to smoke and pray at the same time, wrote the Pope for a definitive answer. One priest phrased the question "Is it permissible to smoke while praying?" and was told that it was not, since prayer should be the focus of one's whole attention; the other priest asked if it is permissible to pray while smoking and was told that it is, since it is always appropriate to pray. The form of a question may even block us from seeing solutions to problems that become visible through a different question.”

Questions might spark discomfort and dissonance. They might also rouse us to the need to reflect on our work and our lives (inseparable as they are). Cast in this light, something like moral distress isn’t a bad thing, but the beginning of a process of that could be reformative, even transformative.

I’m glad we have CECs. They provide a helpful, unique service within healthcare for clinicians and patients in difficult situations. ASBH proposes a useful method for CEC. However, we can’t outsource our reflection on quandaries and conflicts to CECs. Such turbulence at the bedside could prompt us to swim upstream in our own lives, in our own traditions, to sit under the tutelage of bigger questions and grapple with bigger tensions. Then when we return to our work, we may find that whether the quandaries and conflicts have changed or not, we ourselves are different.

That’s probably a good idea, because there’s a risk of stigmatizing human error as morally egregious, foisting a terrible burden on any clinician who has or will make a mistake.

In this study, 34% of the respondents were clinical ethicists. Other roles (not mutually exclusive) were academic, policymaker, student, fellow, IRB chair/member, or “other.” Nevertheless, we might have reason to believe that what the study says about “bioethicists” in general might also apply to clinical ethicists, although it’d be interesting to see a more targeted study. Does anyone know of one?

I cited from the draft of the third edition of ASBH’s Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation. Where I cited, it seems fairly consistent with the second edition, although please let me know if I’ve overlooked a significant discrepancy.

The nudge-and-wink nature of medicine’s hidden curriculum means medical training programs continue to laud in the classroom virtues like compassion while setting them aside on rounds for the sake of efficiency and metrics that don’t measure them.

If we’re going to be wisely compassionate, we need to school our hearts before the moment of compassion. Oliver O’Donovan has an incisive concern about this virtue: “Compassion is the virtue of being moved to action by the sight of suffering - that is to say, by the infringement of passive freedoms. It is a virtue that circumvents thought, since it prompts us immediately to action. It is a virtue that presupposes that an answer has already been found to the question ‘What needs to be done?', a virtue of motivation rather than of reasoning.”

Generally, but not always. Every once in a while, a shepherd with a sling takes down a giant who trained in war from his youth. Those giants are sustained on the naïve belief of others that mere duration of experience confers wisdom. Someone can have twenty years of experience or one year of experience twenty times over.

As a practicing CEC, I appreciate this post. But let me suggest that medicine faces a similar problem. Classically, the goal of medicine are to safeguard and promote health. But "health" -- much like "morality" -- is a troubled and contested topic admitting of multiple concepts from multiple traditions. One only needs to survey the intellectual traditions of Aristotle, David Hume, and Michele Foucault to see how complicated and value laden "health" can be. There are proper functionalist concepts, sentiment-based concepts, statistical concepts, and normative-social concepts that all come up (and sometimes conflict) in internal med, palliative care, psychiatry, and surgery -- really everywhere in medicine. There are intractable disputes about the status of certain interventions. The development of new biotechnologies pushes the boundaries of our health concepts into puzzling territory. AND YET, we are able to meaningfully practice medicine, come to wide agreement on treatment plans, provide actionable, evidence-based outcomes associated with healing and the restoration of health.

I submit the case is similar in CEC. There are wide and deep differences in opinion about the natural and status of morality, the correct normative system, the moral status of subjects at the margins, and the permissibility of certain treatments. AND YET, there is a lot of agreement about how to approach a case, what process to follow, and what principles should govern a certain course of action. One of the things that struck me as a CEC fellow is how 95% of the time I could converge on the same recommendations as my colleagues who came from very different starting points and worldview commitments. I am not naive to the problems that beset CEC and ethics more generally. But I think we can overstate them in ways that make the practice seem dubious when it really is not. We can resolve most of the morally-laden conflicts driven by value uncertainty that come up in the clinic.

And that should not be too surprising. There is a difference between practical and theoretical reasoning, after all.

Fantastic post, thanks Josh. CEC aren’t very common in Australia, especially outside of paediatrics. Through my work as a pharmacist in paediatrics, palliative care and more recently voluntary assisted dying, I’ve encountered so many scenarios like those you describe, many of which I continue to think about now. To be honest, one of the reasons I left assisted dying because I was concerned we didn’t have these types of CEC roles and ethics boards in place. Anyway, thanks again for a super interesting read.