Notes from a Family Meeting is a newsletter where I hope to join the curious conversations that hang about the intersections of health and the human condition. Poems and medical journals alike will join us in our explorations. If you want to come along with me, subscribe and every new edition of the newsletter goes directly to your inbox.

For those of you just joining, consider starting here to trace how I’ve been thinking about medicine and technology, a conversation I’ve been returning to time and again.

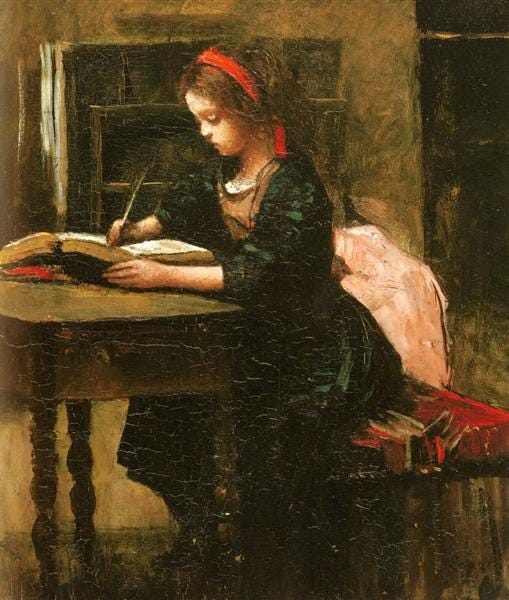

I started writing in the third grade and I never stopped. Stories or essays, haikus or journal entries, there’s something about taking a jumble of something inside my mind and smoothing it out on paper, like so:

Throughout medical school and early in residency, I kept a journal. That has given way to other, less regular forms of writing. Not that my work is in need of less reflection, but that the work is usually less novel and I only have so much time. The majority of my writing time is spent on essays I share here, with a smattering of other pieces elsewhere, public and private.

Why did I start Notes from a Family Meeting?

By sharing something of my own journey, I hope to encourage others, especially clinicians, to write more. A dozen objections may have leapt to your mind just now. It might feel like I’m offering a drowning person a drink of water. “Write more? Are you crazy? I’m up ‘til 11:00 PM finishing clinic notes!” Oh, I know the pain of finishing those notes. Hear me out on the writing more thing though.

All clinicians are writers.

I spend a significant portion of my day at work writing notes about patient care. If you’re a clinician, I’m sure you do too. Clinicians write admission notes, nursing notes, operative reports, radiology reports, or any number of the hundreds of notes that settle into patients’ charts.

Those documents are, as some of these titles imply, reports of what we did and our justification for doing it. Writing clinical documentation is also a means through which clinicians reflect on their work (particularly early in training). An internist who writes every day, “A 56 year old woman admitted with cholecystitis” both writes what they see and sees what they write. Given the rigid form of most clinical documentation, this influence on the clinician’s vision is usually reductive: the internist’s writing doesn’t lead them to see this woman’s military service, her disdain for laundry, her love for her dog.1

My career depends on my writing, just not financially. Without this venue for reflection, my clinical work would suffer. However, my clinical documentation, by necessity, is focused on others. Some (not I) go so far as to expunge the first person pronoun from their writing: “This writer spoke with the patient…” But before I come to write any kind of note or report, I wrestle with myself. The more complex the documentation, the greater the challenge. It’s one thing to reason clinically; it’s another to make a coherent argument that justifies my plan. Most, if not all, clinical documentation requires reflection.

Rita Charon and Nellie Hermann might agree, at least insofar as they have in view overtly “reflective writing” of the kind you might find in this newsletter, in op-eds, and in perspective sections of medical journals:

“Not report but discovery, writing unlocks reservoirs of thought or knowledge otherwise inaccessible to the writer. Representing one's experience in language is perhaps the most forceful means by which one can render it visible and, hence, comprehensible. Writing is how one reflects on one's experience. It is as if that which is experienced has to be somehow ‘gotten outside’ of the person so that it can be apprehended and then comprehended.”

Johanna Shapiro and colleagues share a framework for thinking about “reflective writing” in medical education that pairs two things: private reflection with communal engagement. Through this process, they hope to foster professional development, reflective self-assessment, moral agency and values clarification, narrative competence, empathy, and greater insight into patient care.

Some clinicians can’t help but reflect on the rigors of their practice even in the chart. The language used might suggest mere clinical colloquialisms, but I think they reveal a process of reflection in an environment where little reflection is otherwise possible:

“Mr. Jones refused his insulin.” Why refused? Almost no one uses the less confrontational word “decline.” The former term suggests the clinician’s dissatisfaction and disapproval. By writing this over and over, I wonder if it promotes an adversarial perspective when patients don’t opt for a clinician’s recommendation.

“The family was difficult.” What makes this family difficult? This vague statement might be the only bit of catharsis a clinician has when slinking away from a tumultuous conversation with an angry spouse. By writing this over and over, I wonder if, again, it promotes that adversarial perspective, and also locates the nidus of conflict with families. After all, when do we ever document, “I was difficult at the bedside?”

“Mrs. Lyles is in denial and asks the same questions over and over. She appears to have decision-making capacity though.” The clinician is trying to understand, with whatever rudimentary tools they have, the deliberative processes of someone who is ambivalent and burdened with existential dread. By writing this over and over, I wonder if it shapes a clinician’s one-dimensional perspective of patient decision-making.

If our writing shapes us as much as we shape our writing, wouldn’t it be a good idea to try to learn a few things about how to do it well?

Writing for myself.

The cursor blinks at me. I sip some coffee, check email, and, oh, this other thing is more pressing so I move on to that. The thing I wanted to write never gets written or, if it must be written, is dashed out and minimally revised.

In the blank page I see the swirling morass of my own thoughts. The blank page doesn’t defeat me before I begin; my own thoughts do. This is why

declares the fundamental unit of writing to be the idea, not the sentence. “Writing is thinking,” he writes. Yeah, crafting a sentence is important, but the wrestling match with the idea is the main event of writing.I start to think and questions bubble to the surface: What does this mean? Who cares? How do I connect any of this into something coherent, let alone good? And this is when I’m not distracted! The threat of giving up pulses with each new word. What is the right word here? I delete it and try another. Doubt surges again.

I’m describing the assault of my own thinking even as I write this. Not all my writing is about me or for me (although it may be - e.g., private journaling), but I can’t skip over a crucial fact: it doesn’t matter who my audience is, I write first for myself. Whether it’s a simple progress note, an essay, or a story, moving ideas from my brain onto the page means wrestling with my own heart and mind.

If that’s the case, then I need to make it fair: get the words down before I start wrestling in earnest. I can’t contend with the ever-shifting shadows of my mind. Anne Lamott recommends we jump into the “shitty first draft.” Just let it be bad. I shuffle my internal editor to another room in my skull while I put some words on the page. In Bird by Bird she observes:

“…perfectionism will ruin your writing, blocking inventiveness and playfulness and life force (those are words we are allowed to use in California). Perfectionism means that you try desperately not to leave so much mess to clean up. But clutter and mess show us that life is being lived. Clutter is wonderfully fertile ground - you can still discover new treasures under all those piles, clean things up, edit things out, fix things, get a grip. Tidiness suggests that something is as good as it’s going to get. Tidiness makes me think of held breath, of suspended animation, while writing needs to breathe and move.”

She probably had in mind stories and not essays, but I find it to be just as true in either case.2 Some of my essays start as a collection of disparate words that I lug together into sentences and then heave into paragraphs. At the outset of nearly every essay I doubt myself: there’s nothing here, what am I doing? But I remember this is how I’ve felt dozens of times before and I keep at it.

Sometimes I write from a question, sometimes I write toward a question. Sometimes I don’t which I’m doing until I’ve been writing for a while. Sometimes the answer I think I’ve found introduces me to better questions than what I had before. I appreciate Neil Postman’s perspective on this from his book Technopoly:

“An opinion is not a momentary thing but a process of thinking, shaped by the continuous acquisition of knowledge and the activity of questioning, discussion, and debate. A question may ‘invite’ an opinion, but it also may modify and recast it; we might better say that people do not exactly ‘have’ opinions but are, rather, involved in ‘opinioning.’ That an opinion is conceived of a measurable thing falsifies the process by which people, in fact, do their opinioning; and how people do their opinioning goes to the heart of the meaning of a democratic society.”

Even if I scrap the whole essay, it’s because I’ve learned something I didn’t know when I started. I’ve figured out another way not to invent the light bulb.

Writing for (and with) others.

As I move along, the audience that I had in mind comes to the fore. Having an audience helps. It keeps me accountable and honest. Even if no one reads what I’ve written, knowing my thoughts will sit out there in the world pushes me to clarify them and to consider objections honestly and graciously. Thinking of my audience helps me choose my words and stories.

In the process of writing here, I participate in an ongoing conversation about how we, all of us, see the world. This doesn’t mean truth is relative nor that everyone’s opinion is equal. Some opinions are better informed than others. But I also recognize that I don’t have the perspective from everywhere, I miss things, and I may be mistaken, so it’s good to hear from others. I help myself most when I write what I really mean so that others respond to what are the clearest representations of how I see things. When I read something, the implicit question I’m asking throughout is, “Do I see what they see?” Writing something allows me to hold up an idea and ask others, “Do you see what I see?” Isn’t it amazing that this can happen across time and culture? It might be the closest thing we have to time travel.

Writing publicly, like time travel, is risky. People could think I’m foolish or my opinions are bad. I think part of the unease people have with sharing what they’ve written isn’t just that you’ve made something sub-par, but the inchoate belief that others will suspect you don’t know yourself that well. Like, “Did you even consider this? What were you thinking? Look around, man.” And it’s true: I don’t know myself or the world as well as I could, so writing is both a process of discovery, where I find things within myself and the world, and a process of formation, where I tend new ideas or traits and bolster old ones. Some folks are going to be helpful, others are just going to be trollish. I’m writing with and for the good ones, even (especially?) when they disagree.

When I write publicly, I also try to hold myself accountable to standards, both of writing and of medicine. These, risk and responsibility, are necessary to develop judgment, as

writes in Shop Class as Soulcraft:“On all sides, we see fewer occasions for the exercise of judgment, such as the old-timers needed in riding their bikes. The necessity of such judgment calls forth human excellence. In the first place, the intellectual virtue of judging things rightly must be cultivated, and this is typically not the product of detached contemplation. It seems to require that the user of a machine have something at stake, an interest of the sort that arises through bodily immersion in some hard reality, the kind that kicks back. Corollary to such immersion is the development of what we might call a sub-ethical virtue: the user holds himself responsible to external reality, and opens himself to being schooled by it. His will is educated—both chastened and focused—so it no longer resembles that of a raging baby who knows only that he wants. Both as workers and as consumers, technical education seems to contribute to moral education.”

I’m not so grandiose as to expect that my writing will have a deep impact anywhere. However, I hope if I’ve found something good to write, others will find it good to read. This means I need to write in a space that’s publicly accessible. Passing my work to a journal to lock behind a paywall would mean only clinicians with a subscription would be able to read it.3 For well-known publications like Journal of the American Medical Association or New England Journal of Medicine, that might garner a substantial audience despite the paywall. It’s unlikely people from the general public, and patients, would see it though. The possibility of a wider audience is part of what led me to Notes from a Family Meeting.

“Sour grapes,” some might say. It’s true I’ve not published in either of those journals nor any mainstream outlet where you might find other clinicians writing. It’s also true I’ve submitted pieces to those journals and others only to have them rejected before or after peer review. Given the reality of academic publishing, I needed to make a decision: with the finite slice of time I have to give to writing, how is that time best spent? When submitting to a journal, I spend nearly as much time preparing a piece for submission as I do writing it. Yes, I may benefit from the suggestions of peer review (if it makes it that far). Yes, these journals have a built-in audience. Yes, publishing there would lend credibility to my writing. And yes, if ever I were published there, I would contribute to an important institution. And yet, the burdens, for me, usually don’t outweigh the benefits.

I’m not against publishing in journals like these. I still occasionally try. I also cite academic papers throughout my essays and so my writing is indebted to them. But I want to spend my time writing, not trying to publish.

How do I write?

highlights that, like many other professions, writers need “sufficient resources, time, and motivation” to do their best work.My motivation to write has always been high, though the tyranny of the urgent has sometimes forced me to prioritize other things before it. Because my motivation is high, I set aside time to write. If my motivation were low, I imagine I’d find it hard to justify setting aside any time.

I’m grateful to have the resources to write. This isn’t just my computer. I have access to an academic library where I can read basically anything, I have a career that lends itself to experiences worth writing about, and I belong to a faith tradition that values close reading of the Bible. Paying attention and learning to read well has helped me write. These resources also boost my motivation; without them, I’d find it harder to prioritize writing.

We all have the same twenty-four hours. We all have time. Writing might not be your priority right now. That’s fine. I can’t prioritize everything others recommend either. It helps me clarify my commitments when I admit that I’m prioritizing one thing over another, though, rather than blaming the number of hours in a day. The time is there if you want to use it.

I’m also challenged by this reflection from Oliver Burkeman about reading. It applies just as well to writing:

“People complain that they no longer have ‘time to read,’ but the reality, as the novelist Tim Parks has pointed out, is rarely that they literally can't locate an empty half hour in the course of the day. What they mean is that when they do find a morsel of time, and use it to try to read, they find they're too impatient to give themselves over to the task. ‘It is not simply that one is interrupted,’ writes Parks. ‘It is that one is actually inclined to interruption.’ It's not so much that we're too busy, or too distractible, but that we're unwilling to accept the truth that reading is the sort of activity that largely operates according to its own schedule. You can't hurry it very much before the experience begins to lose its meaning; it refuses to consent, you might say, to our desire to exert control over how our time unfolds. In other words, and in common with far more aspects of reality than we're comfortable acknowledging, reading something properly just takes the time it takes.”

If writing is thinking, then when we take the time to write, we submit ourselves to the speed of thought. It’s slower than I often appreciate.

Writing is revising.

As I said earlier, my first drafts are bad. But now, let me rephrase: my first drafts are good for what they are. They’re developmentally appropriate in the life of an essay. That’s just the expectation, like you expect a small child to crawl and not to walk. But some might have a hard time believing that what they first produce is so far from what they hope that it’s more straightforward to claim first drafts are “bad.” Either way, I remind myself I’m in for revising and re-revising.

Writing a first draft is the hardest step for me because I’m forced to contend with all my information filters: should I include this? And this? And this? All the doubts I mentioned earlier buffet me around. A first draft might be twice as long as the final draft and it can feel unwieldy. A reverse outline - taking the draft and writing an outline from it - is a helpful tool to navigate a long essay. The reverse outline helps you to see where ideas flow into one another, where you’ve repeated yourself, and where things don’t fit.

My favorite part of writing happens once I have the big ideas in front of me. I sharpen the language, interrogate the ideas, and add color. I move things around. I delete things (and maybe save them for another essay). There’s great pleasure in feeling like I’m making a paragraph clearer by deleting a word or a sentence. If I didn’t already, I also figure out where I can weave in a story or some pictures to ground the abstract ideas. This is sometimes where I’m surprised by what I’ve written: “Oh! This is what I really meant” or “Oh, I’ve been mistaken about this.”

I’ve heard some people loathe this part of writing. Maybe it’s because they suspect everyone else’s final draft falls out of their brain as is, and so they’re disappointed when their own writing requires revision. Well, that’s not the case for me. I’m not sure that’s the case for anyone. Writing is revising.

Habits for a practice, habits for a life.

In Teach Like a Champion, Doug Lemov describes the importance of developing habits to aid learning. Education shouldn’t be easy, but it should only be difficult in the right ways:

“We want to optimize their use of [students’] thinking by filling their school days with two kinds of habits: (1) having a way of doing relatively unimportant things quickly and easily and (2) having a way of doing important things well and in a way that channels the greatest amount of attention, awareness and reflection on the content.”

If I sit down to write but I have no habits, I’m liable to struggle with the smallest of tasks: should I use paper or a computer? If paper, a pen or pencil? Is my desk a mess? If a computer, which program? How do I research and store information I use in my essays? By the time I start to write, I’m so fatigued that I give up after a few minutes. However, because I’ve developed some habits, I can do just what Lemov recommends: focus on what matters most.

Helen Sword provides a helpful way of thinking about writing which she describes in terms of “BASE habits.” I only recently learned about these so I haven’t at all crafted my own habits with these in mind, but I find them helpful to consider my work. She offers a little quiz to find out the structure of your own habits.

Throughout her book, she documents interviews with various academic authors in how they cultivate these habits to hone their craft of writing. Spoiler alert: it turns out there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to writing, as her book recounts again and again.

Behavioral habits. Successful writers carve out time and space for their writing in a striking variety of ways, but they all do it somehow. (Key habits of mind: persistence, determination, passion, pragmatism, "grit.")

Artisanal habits. Successful writers recognize writing as an artisanal activity that requires ongoing learning, development, and skill. (Key habits of mind: creativity, craft, artistry, patience, practice, perfectionism [but not too much!], a passion for lifelong learning.)

Social habits. Successful writers seldom work entirely in isolation; even in traditionally "sole author" disciplines, they typically rely on other people-colleagues, friends, family, editors, reviewers, audiences, students—to provide them with support and feedback. (Key habits of mind: collegiality, collaboration, generosity, openness to both criticism and praise.)

Emotional habits. Successful writers cultivate modes of thinking that emphasize pleasure, challenge, and growth. (Key habits of mind: positivity, enjoyment, satisfaction, risk taking, resilience, luck.)

Because Lemon and Sword use the word differently, I understand a “habit” to be an actual behavior (e.g., I have a habit of reading medical journals every morning), whereas “habits of mind” are virtues in the sense that they’re characteristics that allow a practice to accomplish it’s purpose.

I read this list and see that writing requires persistence, determination, passion, and so on. That’s pretty intimidating. I have less-than-stellar supplies of those things. But writing also cultivates persistence, determination, passion, and all these other things - and it’s a relatively safe venue to do so. These can also be mutually reinforcing: so collaborating in writing keeps one determined (through accountability) and heightens enjoyment.

Writing Medicine, Writing Life

My motivation for sharing all this is a bit selfish: I hope to see more clinicians writing in open spaces so I can benefit from reading them. I hope to see more conversations outside of academic journals and conferences. I hope to see more translation between academic medicine and broader communities (both clinicians and others). I know you’ve got interesting things to share!

Writing Notes from a Family Meeting has been both fun and meaningful for me. If you think you might feel the same, dive in. If you’re already writing something, feel free to share it.

Scribes (human or artificial) promise to free clinicians up to do more “real medicine.” I’m not sure if the evidence bears out that this happens. Likewise, many clinicians rely on templates and copy-and-paste to craft the majority of their notes. Either of these strategies are themselves formative insofar as they subvert the usefulness of writing in helping us to see and think.

At this point in my career, it’s not true for clinical documentation. Usually my first draft is my final draft, unless I’m writing a complex ethics consultation note. But early trainees certainly need to hone their skills in clinical documentation and while they might not get to re-do today’s progress note, they can improve it tomorrow.

I realize other writing is behind a paywall too - from the NYT to some Substacks. I don’t hold it against people for doing that. It just hasn’t been something I’ve decided to do with my own Substack.

Writing is a beautiful craft. I also enjoy editing and through the editing process watching a persons full voice unfold. I enjoy reading newsletters/writings such as this, where someone considers aspects of our work in this instance in a deeper way. Where we can challenge ourselves without negativity and ask ourselves why we do something, why we do it this way, and what it means.

I loved how you brought up the word refused. For a long time I have found that word very harsh and never really explains why someone doesn't want to take or participate in something. As is the phrase "they are a difficult patient or family". They may not consider themselves difficult at all. I have always thought that we are the ones who are having the difficulty, and once again, assuming someone is difficult is not understanding the person's circumstances or what may be going on for them. I don't think for a second that it's always our difficulty, but sometimes I think we are quick to label, and then that label gets handed over, like a poison chalice or a curse. We, within our workplaces, with all of the processes and protocols that are rigid in a way, and we assume in many ways that people will just fit into our ways of working.

Being from a nursing background, I have found this style of reflective writing almost absent from nursing. Maybe I am not looking hard enough or maybe it doesn't cross my path. I see many more of my medical colleagues write and reflect like this: questioning practice, questioning approaches, and I enjoy the writings, the ponderings and find it a wonderful and generous offering, for when we write, we make ourselves open and vulnerable. We put the spotlight on ourselves, not to say look at me but to show that we are deep, considered, thoughtful people who are not perfect (never will be) and experience challenges, often every other day.

Maybe the other benefit of writing is inspiring others in our field to write. As you said, all of us in health are writers and maybe if we actually told our own stories, well who know what that would do.

Many thanks for your ponderings!!

I love this for so many reasons. Really speaks to me and my process. Thanks!