Notes in the Margin - 19 June 2025

Notes from a Family Meeting is a newsletter where I hope to join the curious conversations that hang about the intersections of health and the human condition. Poems and medical journals alike will join us in our explorations. If you want to come along with me, subscribe and every new edition of the newsletter goes directly to your inbox.

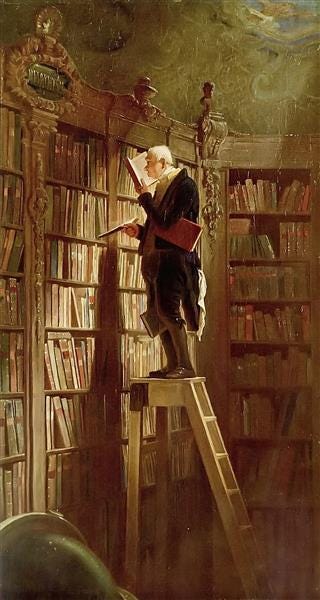

Every so often, I’ll share things I’ve been reading with a few words of mine scribbled in the margins. If you have something to share, please do! The comment section is open.

These authors posed ethical dilemmas to commonly used LLMs and a human ethics consultant to compare and contrast their responses. The whole idea for this is predicated on the idea of an ethics consultant as an expert, tie-breaker, or enforcement officer, and overlooks the role of ethics consultants in cultivating spaces of moral growth and deliberation, not just mere info transaction.

It scares me how excited you are about A.I.

From

: “What I am saying is that we are being trained to throw ourselves away. It has become normal to waste our time, to rot our brains, to end our lives. Having forgotten who we are, we hand over our birthrights — reason as an integrated faculty, relationship as the meeting of mortal and moral subjectivities — with little more than a shrug.”An AIDS orphan, a pastor and his frantic search for the meds to keep her alive

An intimate story that puts a human face on the statistics tracking the fall-out of recent US federal policy decisions.

Matthew Tyler offers helpful advice on “how to train your doctor.” I’ve not thought of “false hope” the way he describes it here. I do think patients can also be self-deceived as they refuse to or cannot interrogate the source and object of their hope. What we do with that depends on what we believe hope is supposed to do. If hope is merely a coping mechanism, then it doesn’t matter much if the object of hope is a lie. What matters is that it helps you cope. However, if hope is meant to draw you into an important existential task that, while steeped in uncertainty is also grounded in reality, then it matters whether it’s false or not. “False hope” is false in the same way a compass can be false, leading one astray. Hope in this sense is also linked with responsibility: hope motivates our behavior and it’s irresponsible to not grapple with our motivations.

Do patients without a terminal illness have a right to die?

Killing patients pits the duty of the clinician against the mandate of a liberal state. When I say “liberal,” I mean it in the sense that the final arbiter of value and meaning is the individual’s choice. Killing those without terminal illness is the inexorable expansion of this logic to assuage the cognitive dissonance that does not allow death to be withheld from anyone. Eventually the arguments terminate either in death available to anyone who makes the autonomous choice and/or death provided non-voluntarily to those who cannot consent but nevertheless suffer so as to not create a double-standard whereby their suffering is invalidated. Neither of these paths are good for clinicians, patients, and society to take.

Outsourcing thought with Nita Farahany

This conversation dives beyond the technical concerns with AI into, as Farahany puts it, what it means to be human. What are we expecting from our work? What are we outsourcing and what shouldn’t we outsource?

Medical AI and clinician surveillance - the risk of becoming quantified workers

Do we really want the walls to listen?

Some may believe statements of faith are too antiquated or idiosyncratic to serve in broader discussions about innovation and modern technology. To the contrary, statements of faith help us to draw on institutions and traditions with thousands of years of wisdom in meditating on the human condition: "The commitment to ensuring that AI always supports and promotes the supreme value of the dignity of every human being and the fullness of the human vocation serves as a criterion of discernment for developers, owners, operators, and regulators of AI, as well as to its users."

I can’t believe I only just recently discovered this fabulous paper. The authors provide guidance on how to titrate conversations to help patients come to terms with their death, gently helping people explore what it means to live well despite everything else that’s going on, which is really the essence of palliative care. I already know I’ll return to one striking metaphor again and again: “Words, like medications, have different potencies. For example, the phrase ‘‘thinking about dying’’ (100 mg strength) is more explicit and may be more challenging for patients than vaguer phrases such as ‘‘thinking about getting sicker’’ (10 mg strength) or ‘‘thinking about the future’’ (1 mg strength). We often begin discussions with weaker words and then judge howto increase the potency by matching the language the patient uses. We aim to promote a feeling of safety for the patient by reflecting and following their lead.”

From the Archives

Here's something, only a little dusty, that new readers may not have seen.

Clinicians are always looking for the edge to improve their practice by streamlining processes and becoming more efficient. However, all the technique in the world won’t tell us what should be the object of our attention, and how we sustain attention even once we’ve honed all our techniques. How should we attend?

Paying Attention

I’ve never been lost in the woods. I enjoy hiking but I stick to the marked trails. I have, however, been lost in the hospital. Any patient’s family member can empathize, but thankfully by the end of intern year, I knew all the quickest routes from the ED to any patient’s room. Even then, even when I could manage rounds like a rigged game of chutes and …