Geraldine Jackson was used to a life with diabetes.1 She was more familiar than most with doctor’s appointments, waiting rooms, blood work, and lines at the pharmacy. While she didn’t structure her day around insulin, it did have its unique place in her routine. But then she was diagnosed with breast cancer. More appointments, more waiting rooms, more blood work, more visits to the pharmacy. Add to that more phone calls with the insurance company, more visits to the emergency department and more of everything. An entire meal could be dedicated to her medications alone, and her week was scheduled based on what other people recommended. For her health, of course.

Not just that, but it was the nurse who never made eye contact, the doctor who interrupted her, the surgeon who rushed through the description of her mastectomy. Her cancer received excellent care, but she was secondary. The sicker she became, the more dehumanizing she found her encounters with the people who were tasked to care for her. She felt simultaneously like a machine and an animal, tuned up and then herded here and there.

It was this same system that boasted whole person care. Some of these doctors and nurses attended lectures on caring for people in their entirety - their emotions, their families, their hopes, their “social determinants of health.” People are, after all, more than their diseases. Because everything is seen when providing such total care, nothing is missed. We can humanize the clinical encounter by knowing more of our patients as people. Everything can be managed, or at least studied. Data, so much precious data, can be collected and collated.

Such total care touches everything because health touches everything. We experience everything in life through our bodies. By association, then, the authority that clinicians, and particularly physicians, wield is unique. This is the currency of the total institution: health is the passage through which we touch anything else, and so those with the authority to define, support, and restore health are strange gatekeepers.

Disadvantages and dangers might leap to your mind as you read this. Just look at Ms. Jackson’s slog through her totalized cancer care. Her life runs on the oncologic agenda. If you’ll be patient with me, let’s peek into one of those dangers that are more subtle than the rest.

What It Means to Care About Wholeness

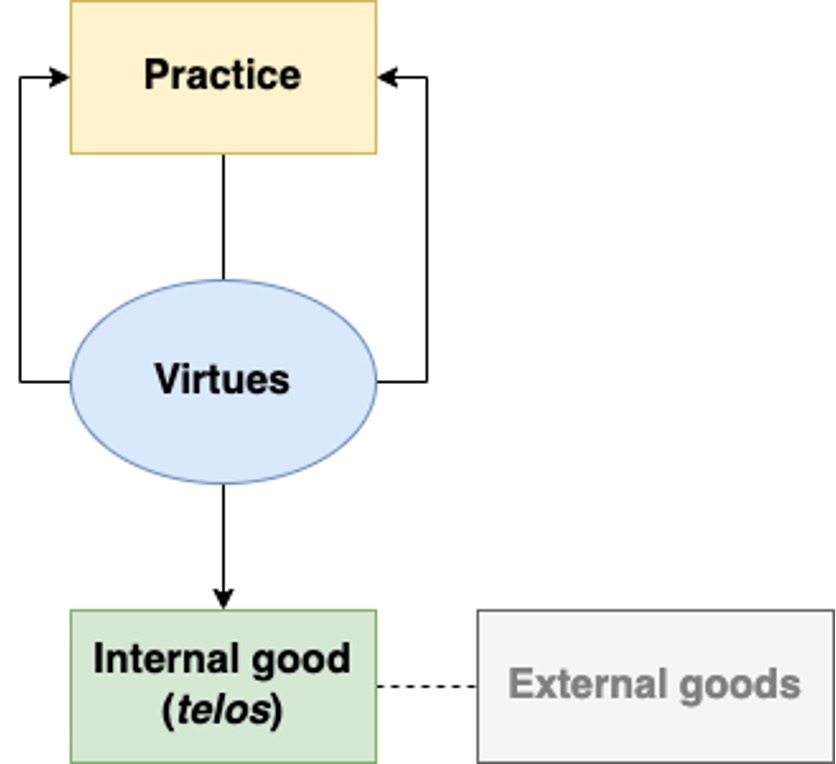

Alasdair MacIntyre, in After Virtue, described a basic framework that we can use to understand medicine. I’ve sketched it out here:

Medicine is our practice, aimed at the good of health. Our pluralistic culture makes us shy to talk about the particularities of virtues, but these are simply characteristics that a practice requires to achieve its internal good. For medicine, these are things like compassion and wisdom - a discussion for another time. The internal good is something that can only be achieved by pursuing excellence in the practice itself. By definition, “good medicine” is that which supports or restores health. External goods, on the other hand, aren’t unique to the practice but may accrue as a pleasant side effect - like earning money or a reputation. Aim at the external goods through the practice of medicine and you’ll miss health; aim at health, and you may get the external goods thrown in.

The virtues needed to pursue someone’s health grow among the people and tradition of a community. Gerald McKenny observes, “Such a tradition will possess two characteristics … First, it will provide an account of how bodily health is related to the ends of life, what degree of health is necessary to attain those ends, and how suffering thwarts or helps one to realize those ends.” Which means we’d do well to figure out what health is for. Health is just one good thing in life among many, though it is special in that it’s the good thing through which we experience any other good thing, as I mentioned. It’s important to understand the relationship among health and other goods.

McKenny goes on: “Second, when technology brings new areas of bodily life into the realm of medical intervention, both those ends themselves and certain norms and prohibitions will place limits on the pursuit of health and the means by which its pursued.” When we preserve the relationship among the practice, the virtues, and the aim of medicine, the system is stable, like a beautiful garden. It doesn’t make it easy, but it is resilient to all kinds of environmental changes, and it works. Like a garden, the things that grow there need enough water, the right soil, and protection from pests. The value of limits is apparent in gardening, but the fevered desire to relieve ourselves of the human condition makes us less willing to appreciate limits in medicine. So we chant over each new technological development: “If you can, you should.”

Nevertheless, health is still about wholeness. We are really more than our diseases, our frailty, our vulnerability, and our mortality. In one sense, then, a clinician, when practicing well, sees and pursues such wholeness, but within the limited bounds of the goals of care, the tension between the individual and the common good, and general, separate moral considerations (e.g., don’t kill).

So what’s wrong with whole person care?

Whole and Total Care

We most realize we have health within ourselves when we’re least aware of it. Defining it in the bodies of others requires consensus that, in many ways, our culture can’t sustain. It’s easier to agree on what constitutes disease instead. This is a local manifestation of a much broader movement extending back to the Enlightenment, in which society sought to shrug off the domineering (and often abusive) authority of the state and the Church and crown the individual with that power instead, which is easier said than done, as MacIntyre observed:

“The problems of modern moral theory emerge clearly as the product of the failure of the Enlightenment project. On the one hand the individual moral agent, freed from hierarchy and teleology, conceives of himself and is conceived of by moral philosophers as sovereign in his moral authority. On the other hand the inherited, if partially transformed, rules of morality have to be found some new status, deprived as they have been of their older teleological character and their even more ancient categorical character as expressions of an ultimately divine law. If such rules cannot be found a new status which will make appeal to them rational, appeal to them will indeed appear as a mere instrument of individual desire and will. Hence there is a pressure to vindicate them either by devising some new teleology or by finding some new catagorical status for them. The first project is what lends its importance to utilitarianism; the second to all those attempts to follow Kant in presenting the authority of the appeal to moral rules as grounded in the nature of practical reason.”

We must contend with a significant conflict between utilitarianism and rules-based ethical reasoning (called deontology). There are certain things we could do to maximize utility but might violate a right or duty; likewise, honoring a right or duty might yield a less-than-ideal outcome. Which do you choose? MacIntyre goes on to argue that the tension between these two projects resolves in asserting individual preferences, which he calls emotivism.

Principlism, traditionally articulated by Beauchamp and Childress, rose to the fore in the late 20th century as a way that could walk between utilitarianism and deontology but doesn’t appear grounded on mere preference. Beauchamp and Childress describe four principles as ways of using the “common morality” to address dilemmas in biomedical ethics.

Though they resist that their perspective supports this, the practice of medicine at the bedside elevates respect for autonomy above beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. This seems true to me in my own personal experience, in the history outlined by MacIntyre (also documented elsewhere by others like Carter Snead and Charles Taylor), and in cultural developments within the world of medicine (justifying, for example, assisted suicide and euthanasia, inequitable health practices, quackery like the approval of minimally beneficial and maybe overtly harmful medications like aducanumab, and so on). On that last point, it’s not just that clinicians are willing to offer these, but that people demand them; patients demand treatment for their own reasons and that is often sufficient to get it.

The rabbit hole goes deeper, but maybe that sketch is sufficient to make the case that in modern medical reasoning, what we aim for is no longer health, but the autonomy of our patients. The quest for whole person care is an attempt to know more of the patient to realize more of their autonomy. Clinicians become instruments in the hands of other people for actualizing their desires (never mind clinicians’ own autonomy). Most of the time, this yields some benefit to health because most people access healthcare when they’re truly sick. Ms. Jackson wanted her breast cancer treated and that also aligned with pursuing her health. This supplanting of health for autonomy has worked so well because the outcome appears similar in so much of day-to-day medicine.

I would suggest, though, that it’s this subtle change that destabilized the practice of medicine. Those virtues you need to satisfy someone else’s desire might be different than what you need to support their health. You might do one thing for a patient and then turn around and do the exact opposite for another. You might help one patient die and another live, which spreads your expertise thin across the spectrum of all those customers you’re serving. You may need to unmoor yourself from the tradition of practice that had for so long pursued health. Where there were limits now there are none; frontiers are open, with new dangers haunting those lonely valleys. We have only barely begun to consider what it means to use medicine in this new way.

We’ve seen this in our reasoning during the pandemic, where clinicians have attempted to pivot into a broader concern for public health but much of the general public, taught by their doctors in clinics and hospitals, continue to rely on the satisfaction of their individual desires. Clinicians have lacked the moral imagination necessary to make a robust case for managing this tension; many have simply provided more information with the hope of convincing the individual to behave accordingly: “follow the science.”

Efficient Care

Medical technology is like Agent Smith in The Matrix. It metastasizes and has its own agenda, even if it isn’t human or alive. Don’t get me wrong: medical technology has brought untold benefits to humanity (albeit unequally). My family and I are personal beneficiaries. Still, technology is neither entirely good, entirely bad, nor entirely neutral. It’s something of a pharmakon, capable of being both remedy and poison. It’s also capable of producing ripples that reach unexpected places. Who could have predicted the advent of chronic critical illness with the invention of the ventilator? This pseudo-agency of technology is best captured by McKenny: “…the very technology that originates in the effort of the modern subject to bring the external world under his power ends with the power of technology to recoil back and destroy or radically refashion the very subject whose power it is.”

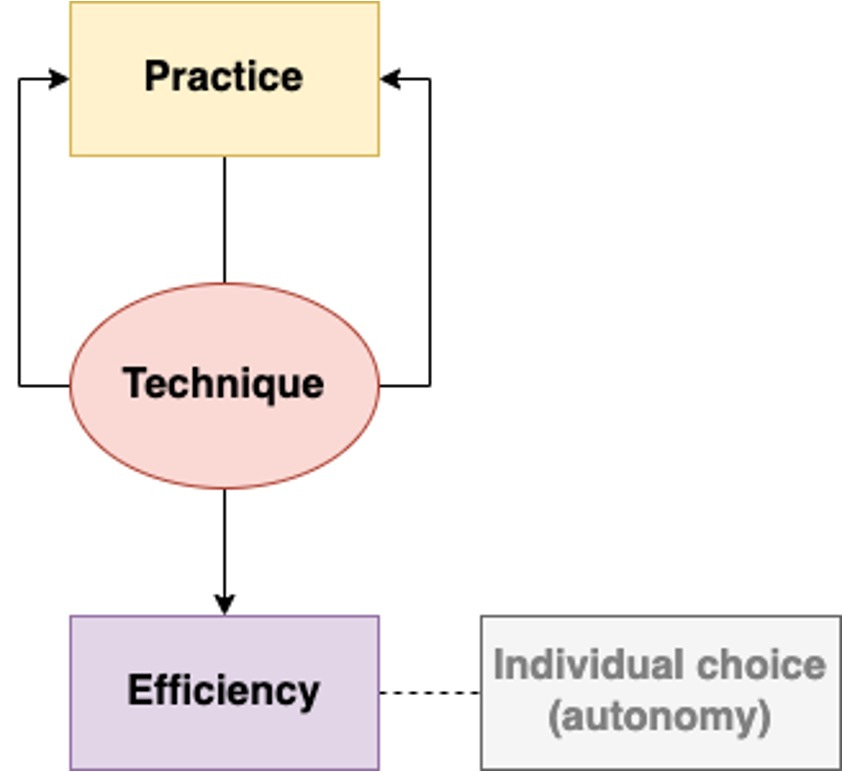

To someone with a hammer, everything looks like a nail. The hammer did that to them. The inventor of the hammer likely didn’t intend to turn the world into nails. And so it is with the chemotherapy, the CT scanner, the scalpel, the DSM, and so on. Technology carries ideas, even whole stories, that causes it to grow around and within us. It grows beyond its intended use. So we look to technology to solve all sorts of problems. We think about ourselves differently now that we’ve seen our genome and are pondering what it might be like to modify a gene here or there, or see our thoughts as the firing of neurons and migration of neurotransmitters. We hobble together some technology to augment our practice and help our patients, and we wind up with this:

You might think I’ve misunderstood something. I’ve drawn that the modified practice of medicine results in, even aims for, efficiency, not autonomy. But this is the trick we’ve played on ourselves. By trying to replace health with autonomy as the purpose of medicine, we destabilized the system at a time when, as Jacques Ellul and Neil Postman have documented, technique in service to efficiency was on the rise. I use the term “technique” the way Ellul did, to describe something that aims entirely at efficiency. In situating the individual as the source of moral authority, we’ve done away with any consideration of ends and focus entirely on means. The soil is perfect for the seed of efficiency to take root.

As we consider this idea of whole person care, consider this warning from Ellul:

“Technique cannot be otherwise than totalitarian. It can be truly efficient and scientific only if it absorbs an enormous number of phenomena and brings into play the maximum of data. In order to coordinate and exploit synthetically, technique must be brought to bear on the great masses in every area. But the existence of technique in every area leads to monopoly.”

Put in the terms we’ve been discussing, medicine’s efficiency is made perfect only when it measures and manages everything. Total care, in this way, is totalitarian. Now, you might balk and say, even if medicine measures everything, it’s still up to the individual to decide what to do with that information. One of the rules of The House of God would reply: if you don’t take a temperature, you won’t find a fever. Posed less cynically, when you measure something, you’re forced to reckon with what you find. With some piece of information we may decide path A or path B, but perhaps we were better off not being posed with the choice in the first place.

That also assumes all this measuring will actually yield something useful. Postman was less optimistic:

“Information has become a form of garbage, not only incapable of answering the most fundamental human questions but barely useful in providing coherent direction to the solution of even mundane problems. To say it still another way: The milieu in which Technopoly flourishes is one in which the tie between information and human purpose has been severed, i.e., information appears indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, in enormous volume and at high speeds, and disconnected from theory, meaning, or purpose.”

I can’t help but think of note bloat within the EMR. More insidious, though, is the dizzying array of jargon and statistics thrown at patients in an attempt to help them make medical decisions. That’s not a good way to go about helping someone, but we’re tricked into it because of the allure of technique.

And so, Ellul again:

“Technique has penetrated the deepest recesses of the human being. The machine tends not only to create a new human environment, but also to modify man’s very essence. The milieu in which he lives is no longer his. He must adapt himself, as though the world were new, to a universe for which he was not created. He was made to go six kilometers an hour, and he goes a thousand. He was made to eat when he was hungry and to sleep when he was sleepy; instead, he obeys a clock. He was made to have contact with living things, and he lives in a world of stone. He was created with a certain essential unity, and he is fragmented by all the forces of the modern world.”

Not only are individuals overwhelmed and transformed by the glut of information rushing at us in this modern era, but respect for autonomy only becomes a side constraint and a cover for serving efficiency. This is most apparent in the practice of clinicians who “get the consent” as expeditiously as possible, sometimes ignoring the possibility that their patient may not fully understand what they’re talking about or appreciate how this might serve or hinder their own health. Other clinicians, when frustrated with their patient’s reasoning, order them to undergo a psychiatric evaluation. Being a psychiatrist myself, I don’t have a problem with that evaluation as such, but I’ve seen it used in an attempt to disarm the patient and deal with a more pliable surrogate decision-maker.

Those are egregious examples, but the situation is more subtle and complicated still, in part because we struggle to understand what an autonomous decision really is. Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby goes into great detail exploring this and the concept of “nudging” in the clinical encounter. Even if we use behavioral economics to absolve some of the more benign shepherding clinicians might have over their patients, the force of technique described by Ellul and Postman motivates clinicians to keep the clinic moving, keep the hospital flowing, and keep matter in motion.

When the practice and tradition of medicine are so off-kilter, we’ll lose a major way of managing all the information we gather when we care for folks. Rather than try to anchor ourselves back on health, we’ll apply technique more rigorously to become more efficient in managing the problems that keep cropping up as a result of this fever. On the one hand, we try to satisfy our patients’ desires, whatever those are. On the other, we work in a system bent toward efficiency that actually degrades and dehumanizes those very same patients (and clinicians). We want to care for the whole patient because we think knowing them better will allow a fuller realization of their autonomy. I worry that will just submit more of who they are to the machine we’ve built that lumbers and lurches further from health with each passing year.

In wanting to know the “whole person,” we want our patients’ secrets, hopes, families - everything. But while we’re caring for the "whole person," we’re just turning their life into one big clinic. Maybe even one big waiting room. Their life will be measured in new ways, better ways, supposedly healthier ways. Their intimate beliefs will be leveraged toward medical decisions. Their whole experience of health (or illness) will be translated into a series of medical decisions, made all the more efficient because the clinicians have dragged the whole person into the clinic. Technique reaches out and touches everything. Clinicians will struggle to make use of it all because we’ve lost sight of health.

Still Human For Now

There are classes that will teach you how to say the right things to appear more empathic. They’re very helpful, particularly for alexithymic clinicians who struggle to identify emotions. In the harried moments of the day, many of us become alexithymic, the urgency squeezing out the apparent luxury of emotional perception, so these classes can be helpful to a degree.

Their weakness is they can carry students into the uncanny valley and leave them there. Empathy becomes just a key to a more efficient clinical encounter, rather than a bridge to meaningful, albeit human and thus inefficient, connection. “What else [but revulsion] could one possibly feel towards something whose form suggests the promise of reciprocal human interaction, but which we simultaneously sense is not real? The same seems to go for empathy: the only thing worse than not having it is being insincere about it.”

Everything I’ve discussed has the patient in view: the endeavor threatens to subsume the individual within the efficient surveillance and management of medical technique. It applies just as much to clinicians who, in this system, become technicians, both of disease and of efficiency. They choose communities of efficiency over communities of virtue, and supplant virtues with superficial replicas, like professionalism. They, like their work, devolve in service to efficiency on the path to burnout (itself a mechanical, individualistic diagnosis).

How can we avoid this? Jeff Bishop gestures toward something helpful: “If we are to prevent all practices in medicine from becoming thoughtless doing, we must once again turn to how we think about what it is that we do.” Not only that we think about what we do, but think about how we think about what we do. We could start here: what led us to supplant health as the aim of medicine, and what has resulted? How can we aim to support and restore someone’s wholeness without submitting all of who they are to the rigors of the machine upon which we’ve only glanced? How can talk among ourselves about health?

Trajectories

Following a meandering reading-path, sharing some brief commentary along the way.

“Evolution of the randomized clinical trial in the era of precision oncology”

Many (most?) cancer clinical trials measure surrogate end-points and are funded by the pharmaceutical industry. What does this mean for front-line oncologists and their patients? Not being an oncologist myself, I’m concerned mostly with the patients. I worry that it will become increasingly difficult for patients to know whether the treatment receiving for their cancer will actually help them live longer or better. Of course we may all believe it will because the trials are reassuring, but the way the trials are constructed by hide the truth of the matter, or else yield what is ultimately a minuscule benefit.

Closing Thoughts

When we no longer know what to do, We have come to our real work and when We no longer know which way to go, We have begun our real journey.

Wendell Berry

Any cases I share are fictional unless otherwise indicated.