Notes from a Family Meeting is a newsletter where I hope to join the curious conversations that hang about the intersections of health and the human condition. Poems and medical journals alike will join us in our explorations.

For those of you just joining, consider starting here to trace how I’ve been thinking about medicine and technology, a conversation I’ve been returning to time and again.

“That must be so hard for you.” Dr. Walker patted Sandra’s shoulder twice with a fully extended arm. Dr. Thomas, the intern in the corner, echoed, “Yes, so hard.” Sandra felt awkward but nodded, dabbing her eyes with a tissue. Caring for her husband had overwhelmed every capacity of love and ingenuity she thought she had. She had gotten maybe three hours of sleep the week before she brought him to the hospital. His behavior had gotten out of control.

Sandra sat on the edge of the hospital bed while Bill slept. Dr. Walker perched over them both, stooping like she might if she were speaking with a child. “So hard,” Dr. Walker said again. “Well, have you thought much about those nursing facilities?” Sandra hadn’t. While she had struggled to care for Bill at home, she also struggled with the feeling that no one here saw him as a person. They said the right things, sometimes, but often appeared harried and distracted.

“I thought I…” Sandra began.

Dr. Walker looked her phone. “Oh! Hold that thought, Mrs. Little.” The physician fled from the room, the intern following silently behind her.

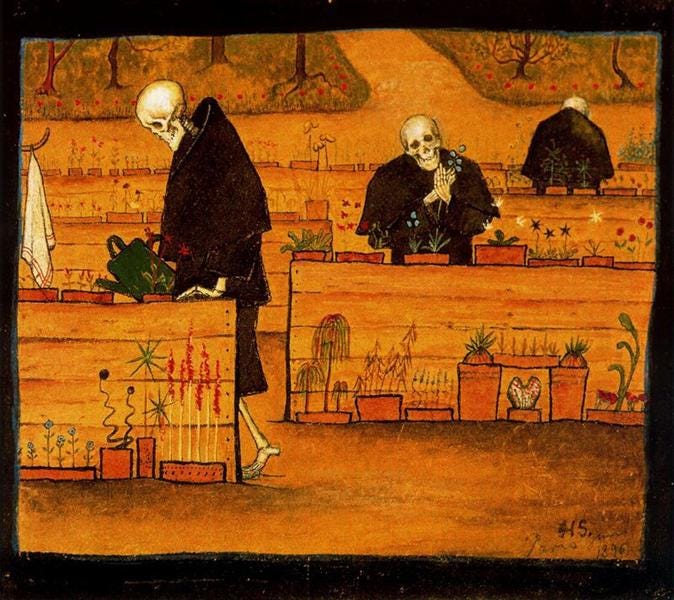

Following Caleb Gardner, I’ve appropriated the phrase “uncanny valley” to include interactions with other humans that lack humanity and instead feel automated, robotic, or wooden. Jerks and anxiety-ridden novices probably won’t be the culprits here. Instead, people who have the semblance of humane compassion or warmth, but falls short, are most likely to induce the uncanny valley.1

The uncanny valley is a symptom, not the problem itself. The experience flags a lack of humane attention, emotional attunement, and moral awareness. Without these, a therapeutic relationship may struggle and patients are less likely to disclose important information, adhere to recommended therapies, and cope with the burdens of their illness.

When I first wrote about this, I explored in some depth the technical mindset that contributes to the uncanny valley in medicine. I want to deepen that exploration, and consider another cause too: inexperience.

Novices and the Uncanny Valley

In most clinical encounters, a novice may struggle to balance attention, attunement, moral awareness, and other clinical tasks (e.g., taking a history, forming a differential diagnosis, budgeting time, etc.). This balancing act is so challenging because they dedicate their working memory to one unfamiliar task at a time. They won’t be able to shift among or integrate other important aspects of the experience. As a result, the encounter feels choppy, laggy, and awkward. If the novice attempts to appear empathic without feeling empathy (because they’re juggling so many things), others might find themselves in the uncanny valley: this person is trying to show empathy but I can tell they aren’t actually being empathic.

The challenge of learning is to offload knowledge to long-term memory so that one’s working memory is free to engage a novel context with agility and creativity. Habit formation, practice, reflection, and social engagement help to facilitate this process.

Habits foster learning by moving routine tasks out of working memory. When we make something habitual, that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant. Rather, it’s so important that we need to make it routine. If you start your day struggling to find your lost pencil, it makes the writing process that much more arduous. If you start the day knowing that your pencil is always ready at your desk, you’re already primed to jump right into the task of writing.

Practice resists forgetfulness, as it takes repeated engagements with new material to encode it into long-term memory.

Reflection develops connections between new learning and what one already knows. Without reflection, you might become a repository for all sorts of knowledge, but that knowledge will lack the inter-connections that signify expertise. Without these connections, you’re less capable of responding with creativity to novel situations where your old habits might not suit the circumstance.

A culture of learning, even a culture of error (where mistakes are expected), sets expectations for what trainees can expect from learner-educator relationships. These tasks highlight the importance of attention in distracting environments - not only to what one attends, but how one attends.

Educators may struggle to respond to these challenges because, as the aforementioned principles of education suggest, the gap between a novice and an expert is not only in the content of their knowledge, but also in how they use and connect that knowledge. A novice may approach each problem anew, dedicating the whole of their working memory to each component, whereas experts perceive deeper structures within the problems, categorize them, and discern when they need to deviate from habituated approaches. Novices need to learn more than content because they

“…are likely to perceive incorrectly or attend to low-value phenomena or use up their scarce working memory searching for the right information. With little knowledge on the topic in their long-term memory, they make far fewer connections. For novices, carefully guided instruction is far more effective. However, too few educators are aware of this distinction. They tend to presume what works for experts is therefore best for everybody.”

How and why one attends to the various phenomena throughout the clinical encounter is itself a moral endeavor as one gives value to some things and ignores or deprioritizes others. Focusing on skill development while neglecting purpose (i.e., the “how” instead of the “why”) masks this moral valence. Given the many layers of the clinical encounter (biological, psychological, social, ethical, etc.), guided instruction from educators and experts can take multiple forms, one of which I’ll describe shortly.

Serious illness conversation training, like VitalTalk and other programs, provides clinicians with tools to have better conversations related to prognostication, goals of care, and advance care planning. When clinicians make the use of these tools habitual, they’re able to devote more of their attention to the emotional and moral valences of the clinical encounter. As far as I know, no one has (yet) investigated how clinicians manage this tension between the cognitive and affective channels of the clinical encounter. Studies rarely elicit patient perspectives on how training impacts their perception of a clinician’s empathy. Even with training, though, humane presence, emotional attunement, and moral awareness in the clinical encounter may not happen because of the uncanny valley’s second driver: the technical mindset.

Technicians and the Uncanny Valley

Jack Coulehan observed how medical training can form a professional identity that may be at odds with the espoused values of the profession. Rather than becoming compassionate and reflective, trainees become unreflective, embittered professionals. One hallmark of a deformation of professional character is the “technical mindset,” which is reductionistic, efficient, and presumptively amoral.

The technical mindset is reductionistic. This isn’t by itself a bad thing. There’s too much about the human body and all the many ways we can intervene on it for any one person to know. Sub-specialization allows us to understand and manage discrete domains of human form, function, and pathology. However, focusing on one part risks losing sight of the whole.

C. Thi Nguyen’s reflection on games clarifies how this goes awry. Life is hard because we struggle to prioritize and live out our values. In contrast, games provide “value clarity”: values in games are easily applicable, commensurate, and rankable. This clarity may tempt us to either make real life situations more like games, or to avoid real life situations that are not game-like. This happens in medicine. Surrogate markers (e.g., creatinine, blood pressure) stand in for more complicated concepts (e.g., organ function and, ultimately, health), which Nguyen calls “value capture.” These surrogate markers are easily measured, tracked, and compared, making them legible to bureaucracies, fast-paced clinical decision-making, and research. Value capture can lead to “value collapse” where the surrogate marker becomes the main focus of activity.

When values have collapsed, pursuing efficiency for its own sake replaces the more meaningful, nuanced purposes of practice, an idea Jacques Ellul called “technique.” This is the second mark of the technical mindset. Practices no longer pursue their primary ends (like medicine pursuing health), but rather serve ever more efficient measurement and production. More areas of a patient’s life are drawn under the scope of medicine not for the sake of holistic care but for medicalized efficiency. The more that is measured, the more can be controlled to nudge the metrics in the desired direction. Reductionism facilitates this process as intangible facets of life (e.g., “health,” “spirituality,” “culture”) devolve into surrogate markers.

Thirdly, the technical mindset is presumptively amoral. Drew Leder argued that the clinical encounter is a “hermeneutical enterprise” in which the clinician “interprets the patient’s signs and symptoms to ferret out their meaning, the underlying disease.” In seeing the clinical encounter for what it is, “we leave behind the dream of pure objectivity. Where there is interpretation there is subjectivity, ambiguity, room for disagreement. The personal and provisional character of clinical judgment cannot be expunged.”

This doesn’t stop the technical mindset from attempting to bend clinical interpretations toward apparent objectivity. Leder described how clinical work progresses through layers of interpretation from the patient’s history to the physical exam to laboratory and radiologic data. This last level is where the clinician attempts to see

“the person-as-ill translated into a series of numbers … Physicians sought to free themselves from the patient’s restricted perspective and the subjectivity of their own perceptions. Only when translated into numbers did the illness seem to take on a fully objective form. Quantitative data – clear, precise, intersubjectively available – escape the ambiguity and bias of the senses.”

Nguyen warned how quantitative data trades off nuance for portability. Leder added that such quantification is an attempt to sterilize the messy moral landscape of the clinical encounter by providing the reassurance of “objective” numbers.

Serious illness conversations can succumb to this transformation too. The technical mindset reduces the conversation into an algorithm through which the chaotic elements of family, emotion, spirituality, and decision-making should be efficiently processed, yielding a clean, institutionally legible decision. Conversation maps are not meant to operate algorithmically, but harried clinicians captured by the technical mindset may use them as such. I have seen clinicians ask a patient about their faith or worries, for example, but then not know what to do with that information. The conversation awkwardly dwindles back toward an amalgamation of other questions about symptoms. Perhaps they hoped that asking about it would somehow unlock the next level in the conversation and move them closer to a decision. That isn’t why those questions should be asked.

If one believes that inexperience is the primary underlying cause of the uncanny valley in the clinical encounter, then the primary response would be to educate clinicians out of this dilemma. However, teaching content alone risks ignoring the formative components of education. The clinical encounter requires clinicians to recognize and respond not only to biological but psychological, social, and moral questions and dynamics. Reducing the clinical encounter to a bare scaffolding of collapsed values - decisions about surrogate markers representing physiology, for example - may lead clinicians to neglect the moral formation that precedes and shapes decision-making and situates biological considerations in the broader context of a human life. A reductionistic account of the clinical encounter may also impair clinicians from viewing themselves as moral agents, diminishing their capacity to appraise their own behavior and the structures in and with which they and their patients interact.

Given that patients and families often acknowledge that there are ethical facets of every decision they make about their health, serious illness conversations engage the moral dynamics of healthcare. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, as the pursuit of health is part of the foundational pursuit of the good life. Clinicians partner with patients in this pursuit as they seek to restore and sustain health. Clinicians and clinician educators who neglect moral formation not only leave themselves ill-equipped to respond to moral dilemmas in medicine but dampen their capacity to navigate the clinical encounter in all its breadth and depth.

One manifestation of this is the uncanny valley which, while not an overtly moral problem, may reveal deficiencies in moral formation (either because of lack of education or because of capture by the technical mindset). Skills alone can’t fix this problem. Even if they possess a skill set for, say, responding to patients’ emotions that arise upon receiving bad news, clinicians may lack the necessary orientation to attend and respond appropriately to the full range of phenomena occurring in the clinical encounter. They may instead be tempted to use communication skills as a means of leveraging their own (collapsed, technical) agenda (e.g., changing a patient’s code status). This could manifest in a clinician who responds in rigidly “appropriate” ways but does not appear to really care about what the patient is saying.

In this frame of practice, a clinician may learn and apply the relevant communication skills but still induce the uncanny valley. They don’t behave in a human way; they behave like an efficient machine, which accords with what Neil Postman wrote when he described the phenomenon of the technopoly: “...we are at our best when acting like machines, and that in significant ways machines may be trusted to act as our surrogates. Among the implications of these beliefs is a loss of confidence in human judgment and subjectivity.” The machine becomes the pinnacle of clinical acumen because “only when translated into numbers did the illness seem to take on a fully objective form. Quantitative data - clear, precise, intersubjectively available - escape the ambiguity and bias of the senses.”

What human clinicians will do to themselves when machines set the standard of care may be more worrisome than what those machines themselves may do.

Responding to the Uncanny Valley

All experts were at one time novices; all masters were once newbies. Every one who wants to learn the craft will grapple with inexperience. The technical mindset, on the other hand, is probably held with ambivalence.2 Sure, it’s good to be efficient, maybe it’s sometimes necessary to be reductionistic, and perhaps we can trick ourselves into believing we’re amoral, and all this might require trading off warmth and compassion. Some clinicians might willingly make that trade, but many do without knowing it.

A virtue-based frame of moral development could respond to both challenges. For the inexperienced, it could help orient education not toward knowledge acquisition for its own sake, which is not the purpose of the clinical encounter, but toward restoring and sustaining health. For those captured by the technical mindset, this frame helps enliven and humanize their practice of medicine by orienting it toward something more meaningful than efficiency for its own sake. A virtue-based frame can help clinicians attend to the moral landscape of the clinical encounter, sustain presence amidst distraction, and care well for their patients, colleagues, and themselves. It also acknowledges that the clinicians themselves, not just their tools, are part of the healing process of the clinical encounter.

Alasdair MacIntyre argued that virtues are those characteristics necessary for practices to achieve ends only they can achieve (which he called the goods “internal” to the practice). The internal good of medical practice is the patient’s health. Technical knowledge of human anatomy, physiology, and medical intervention is necessary but insufficient to pursue this. We need other traits, like fidelity, compassion, and fortitude, to guide the us. Without virtues, the use of knowledge becomes unmoored from any good purpose. It even becomes too unwieldy to use well.

Challenges abound when we try to consider what moral formation could look like in medical education.

First, members of a pluralistic society may remain “moral strangers” without a common moral language, stymying any project before it has even begun. Who gets to decide what?

Second, as we already reviewed, the educational needs of learners mean that moral formation adds to an already crowded educational agenda, one that some clinical educators are ill-equipped to manage if it means moving beyond the merely technical.

Third, it’s not clear whether or how virtues can be taught, though attempts to conform the concept to a behavioral frame have made some promising, concrete suggestions.

Fourth, any pedagogy of moral formation needs to contend with the ever-changing clinical environment and the formative influence of technology and technique. This means adopting a perspective that helps orient and re-orient clinicians to the primary purpose of medicine and what is needed to pursue that purpose.

I think Shannon Vallor provides a helpful response to these challenges. She engages Aristotelian, Confucian, and Buddhist traditions to discern a common way of understanding virtue ethics for a world steeped in rapidly evolving technologies. She recognizes that “technologies invite or afford specific patterns of thought, behavior, and valuing; they open up new possibilities for human action and foreclose or obscure others.” Any worthy response to inexperience and the technical mindset will help clinicians use technology well and discern its formative influences. Given the nature of clinical medicine and the multi-faceted, multi-storied, deep-historied nature of virtue ethics, this is only an introduction to moral formation in clinical training and practice.

Vallor summarizes seven elements of moral self-cultivation drawn from the three traditions (although one can see how these elements relate to other traditions). She emphasizes that “...the temporal order of moral self-cultivation is secondary to its cohesion as a holistic practice. We can conceive of each element as part of an open circle that is to be repeatedly retraced, deepened, and expanded.” And so, “the core elements of moral self-cultivation mutually implicate and reinforce one another not as stages of a sequential process but as interlinking and interdependent parts of a continuous circle.” Therefore, each of these elements works with the others to further refine one’s character - e.g., relational understanding informs, limits, and expands one’s reflective self-examination and empowers one’s intentional self-direction.

While Vallor provides a list of candidate “technomoral virtues,” I’m not going to reproduce it here. The virtues themselves are important, but a community of practice must engage these seven core elements to begin to discern together what virtues best allow their work (in this case, medicine) to pursue its end (in this case, health). That isn’t to say the process precedes the content entirely; the feedback loop established by the engagement itself helps to refine both the process and the content. To start, one should jump in anywhere, but at least in the direction of the end of their practice. Discerning that end is itself refined through this process.

Serious illness conversations provide an excellent area in which to explore this. They’re both instruments of moral development and lenses for revealing it. They become a major venue through which clinicians manifest the uncanny valley or demonstrate humanity. For example, my habits of speech can both shape and reveal who I am (moral habituation). So, too, my means of communication both shapes and reveals how I am bound to others (relational understanding). My communication both shapes and reveals what I perceive (attention to moral salience). Serious illness conversations involve profound existential and moral engagement. To offer training in the skills of communication without situating that training in a broader context of clinicians’ moral development in pursuit of health is to risk inculcating the technical mindset. Every engagement with technology (methods of communication included) is an opportunity for and a challenge to moral development.

Response to an Objection

Someone might behold the success of modern medicine and feel the benefits of the technical mindset outweigh any burdens. They might actually see things the other way ‘round: we should de-emphasize clinician moral development. The way forward is not to embolden clinician values at all. Doing so may unduly restrict access to permissible medical interventions, nudge the patient out of the center of the clinical encounter, and resurrect paternalism. If we’re to unleash the power of medical innovation, it needs to be in service to what patients value, and patients value all sorts of things about their bodies beyond a circumscribed notion of health.

I have at least two responses to this objection.

First, shifting the end of medical practice to something like “whatever the patient values” doesn’t dispense with the need to develop virtues, but only changes what kinds of virtues are needed. In the bureaucracy of modern medicine, for example, desirable professional traits might be “mechanisicity, predictability, reproducibility, and measurability.” It’s unlikely those things will become a part of the formal curriculum of clinical education, but that means their inculcation is even more pervasive through the hidden curriculum.

When medical training selects for these traits, it also diffuses clinical expertise across an array of preferable outcomes (e.g., some patients want to live, some want to be killed, some want an otherwise unnecessary amputation, etc.). Curlin and Tollefsen argue that “insofar as physicians use the technological powers at their disposal to pursue a wide array of outcomes, they necessarily become less expert and skilled at pursuing their patients’ health.” Moral formation, therefore, must accord with particular ends. Given the finite time, energy, and resources clinicians have, their moral formation will be stunted if they attempt to aim for multiple, sometimes competing goods.

Although I said I wouldn’t list particular virtues, I need to go back on that just a bit. Vallor’s framework presupposes two virtues that are worth discussing because they relate to this challenge of identifying and pursuing the proper end of medicine. These virtues are integrity and constancy. By briefly examining them, we can better see how damaging the technical mindset is to clinicians, patients, and their shared endeavor.

Integrity, as MacIntyre defines it, is the limit one sets in their willingness to adapt to their roles. That is, although they act according to the needs of their role, their role does not finally arbitrate their moral agency as an individual. Without integrity, one won’t develop the attention to moral salience required of agency because they’ll forfeit that agency to the authorities governing each role they inhabit. This is the essence of irresponsibility.

Constancy is the single-minded capacity to pursue the same good(s) through time regardless of changing contexts. In medicine, a clinician of constancy orients any aspect of medical care to their patients’ health (and helps their patients seek to orient their health in service to flourishing, of which health is only a part). Without constancy, one remains disoriented about why they are acting in a certain way – should they behave this way in that context or not?

The uncanny valley may be a symptom of losing either integrity or constancy, either because the clinician becomes disingenuous or disoriented.

My second response to the objection is that it fails to appreciate the ways in which we can succumb to the soft rule of technology, argued by Dan Callahan:

“The greatest fear of liberal individualism is authoritarianism. But that fear, reasonable enough, fails to take account of the fact that the power of technology, and the profit to be made from it, can control and manipulate us even more effectively than authoritarianism. Moral dictators can be seen and overthrown, but technological repression steals up on us, visible but with an innocent countenance, and is just about impossible to overthrow, even as we see it doing its work on us. Liberal individualism makes this scenario more easily possible, and that is why it is not a tolerable guide to the sensible use of medical knowledge and technology.”

The promise of technology – medical or otherwise – is that it will expand our capacity to understand and use nature for our benefit. The benefits of the scientific revolution have been immense, but it also left us with an ambivalent relationship with technology. For example, the automobile expanded travel access but also pollutes our environment (directly and via the infrastructure required to sustain its use); social media has created and bolstered communities but also enhanced the reach and scope of misinformation; the ventilator saves lives but has also created the role of the chronically critically ill.

Defending ourselves against this soft rule of technology is not so straightforward as eschewing it entirely, nor can we just pass it over to the individual to let each do with it whatever they will. The goals and values of the individual patient remain valuable, but clinicians have limits in how they should use medical technology in serve to those goals and values. Callahan recognized that hypertrophied liberalism weakens communal pursuits. He argued that

“...the inescapable reality of the kinds of changes that biomedical progress introduce is that they affect our collective lives, our social and educational and political institutions, as well as those tacitly shared values that push our culture one way or another. As an individual, I need to make choices about how I will respond to those changes. But more important, we have to make political and social decisions about which choices will, and will not, be good for us as a community, and about the moral principles, rules, and virtues that ought to be superintend the introduction of new technologies into the societal mainstream.”

An ever-present tension exists between the individual and the community. The capacity to not only sustain such a tension but to thrive while holding it requires intentional moral development. Technique and deference to individual choice are insufficient to use technologies well. With that reality in view, medical educators should prioritize trainees’ moral development. It won’t be easy, but the alternative is that we subjugate ourselves to the pseudo-agency of our technologies and other parties outside the clinical encounter (e.g., the developers of those technologies).

A Conclusion

The uncanny valley can reveal either a clinician’s inexperience or their technical mindset. These problems present an educational challenge: how can we help clinicians to engage in their work with more humanity? It is also a moral challenge: what tension or conflict has arisen among the competing goods of the clinical encounter that makes it difficult for the clinician to act with integrity and constancy? Sometimes it’s a lack of a skill, other times it is value capture and collapse. Serious illness conversations are helpful contexts in which to explore these challenges because it’s within the space of communication that the clinical and ethical so closely, personally, and practically meet.

I’ve sketched an approach for thinking about moral formation that would both guide the clinical trainee toward expertise as well as resist the technical mindset. Venues for future exploration include how clinical educators can foster each of these elements of moral development, how these elements interact with one another in the clinical encounter, what specific challenges exist when engaging with each element, and how individual virtues proceed from practicing within this framework.

I appreciate the feedback I received from Bob Arnold and Farr Curlin on an earlier draft of this essay.

I wonder if, in today’s environment, clinicians will inevitably grapple with the technical mindset at some point in their development and therefore it is a necessary stepping stone toward becoming a good clinician. I haven’t fully considered this, though.