Autonomy, Values, and the Goals of Care

Notes from a Family Meeting, Vol. 3, No. 1

Welcome to the third volume of Notes from a Family Meeting! It’s not really the third volume, since many of the editions of the first volume were just selected readings I sent to my mentees at the time and transferred over to this platform. Wherever we are, I’ve enjoyed working out my thoughts in this space, in conversation with others. I hope you’ve benefited in some way too. Here’s to another year. If ever you want to ask a question or make a comment, you can just reply to the email you receive.

For every parcel I stoop down to seize

I lose some other off my arms and knees,

And the whole pile is slipping, bottles, buns,

Extremes too hard to comprehend at. once

Yet nothing I should care to leave behind.

With all I have to hold with hand and mind

And heart, if need be, I will do my best.

To keep their building balanced at my breast.

I crouch down to prevent them as they fall;

Then sit down in the middle of them all.

I had to drop the armful in the road

And try to stack them in a better load.

Robert Frost, “The Armful”

It would be an oversimplification, but a revealing one, to speak of healthcare as a series of decisions. What it reveals is how much control we (as both clinicians and patients) assume we have, for we only say we have a choice when we have control. But it’s an oversimplification because the existential crises of injury, illness, suffering, frailty, vulnerability, and mortality thrust us into situations where choice is tragic. The most terrifying decisions might involve sacrificing part of ourselves to survive, or accepting that death may come because we find too burdensome those things intended to help. Even decisions where the risks are low and benefits nearly guaranteed submit us in an unpleasant way to a process that we wouldn’t have wanted in the first place.

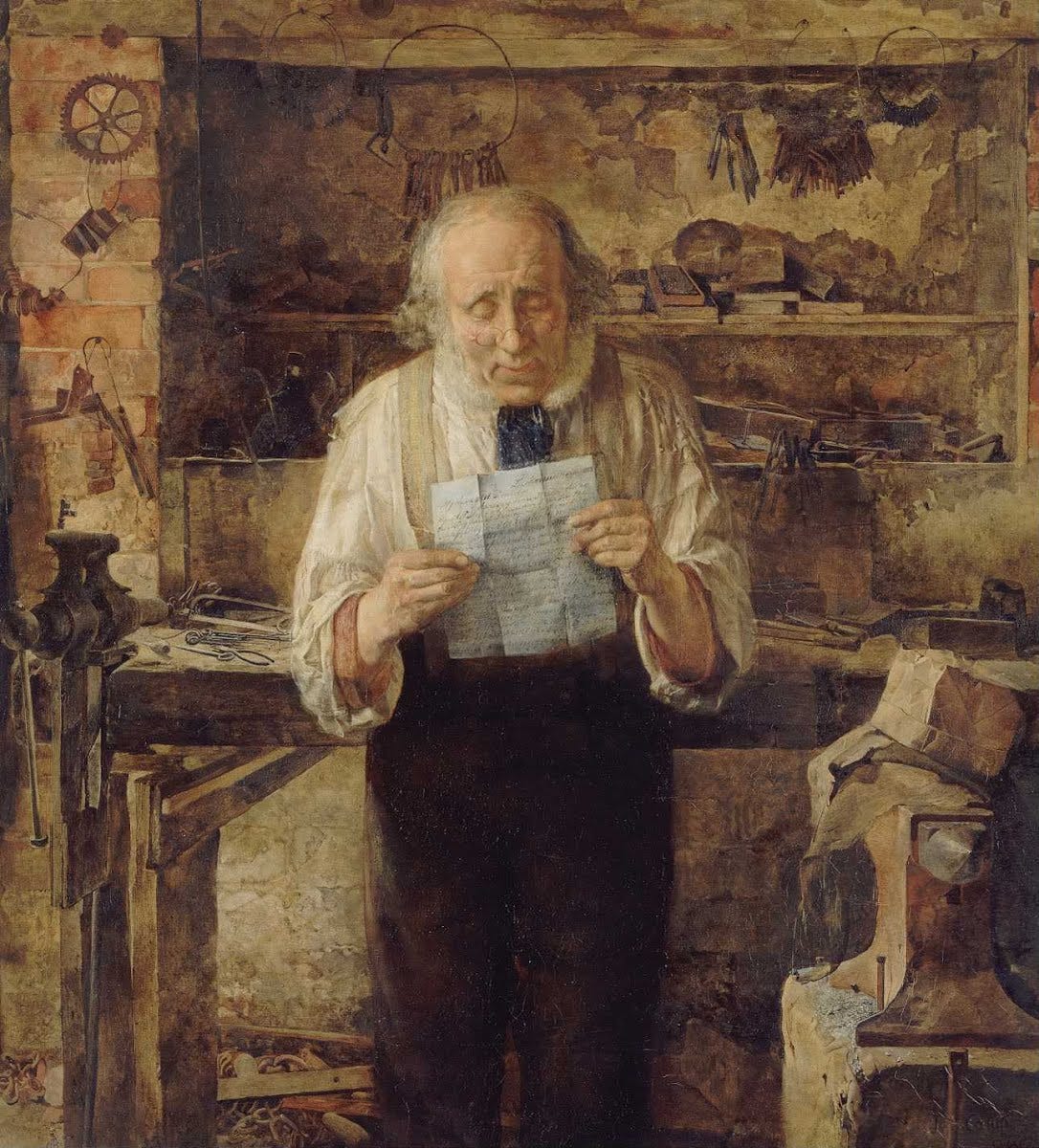

Still, decisions remain, so clinicians try to understand what patients want. Our patients, like Robert Frost in his poem, struggle to hold on to all they love and perhaps have taken for granted. Eventually, in a moment of weakness, confusion, or distraction, they drop them. Maybe they’ll start over, but they’re in the middle of the road. What will they pick up to take with them? What will they leave behind? Who will help?

As companions with our patients on the road toward health, it seems benign to help our patients get what they want, or especially what they most value. This seems a good thing to do irrespective of health. There are plenty of examples of this already, as Eric Mathison and Jeremy Davis observe. Clinicians promote their patients’ values quite apart from health through:

Project-based interventions: These are things like surgeries to preserve limb function in an athlete when surgery wouldn’t normally be the preferred management strategy.

Optional function interventions: e.g., contraception.

Moral interventions: e.g., living organ donation, which does nothing to serve the donor except to provide them a venue to manifest their altruism.

Aesthetic interventions: e.g., elective cosmetic surgery.

Mathison and Davis list other procedures that span several of these categories, like elective abortion and gender confirmation surgery. Ultimately, they contend that medical technology is used for all sorts of purposes that may not (always) aim at health. Given that, there are opportunities to expand the use of medical technologies in other ways: toward assisted suicide and euthanasia, as is already done, and toward enhancement beyond what they already described. If I want a stimulant so I can do better on a test, why shouldn’t my doctor write me a prescription - of course taking into account all the incumbent risks of the medication? It’s up to me to discern if those risks outweigh any benefit I might get from the stimulant anyway. More fantastically: if I want to edit my children’s genetic code so they could be more athletic, smarter, and more beautiful, why shouldn’t I? This is the stuff of post-human dreams, but increasingly more science than science fiction.

The question of whether we should only use medical technology for health helps us see how amazing health really is. Health is unique among all the good things in life for it’s the good through which we experience any other good. Our health is integral to how we interact with the world, others, and ourselves. It’s the means through which we act on the world, and therefore the medium through which our autonomy manifests.1 Insofar as we need our bodies to do anything with our lives, they become instruments of our values. This means that health is not the purpose of human living. Health is a means to something greater than itself.

But none of us have perfect health. Not only because we’re frail, vulnerable, and mortal, but also because non-pathological limitation is baked into the human condition. Fredrick Svenaeus remarked, “…I belong to the world just as much as the world belongs to me. In the same way I also belong to my body. … The body is alien, yet, at the same time, myself. It involves biological processes beyond my control, but these processes still belong to me as lived by me.” This uncanny unhomelikeness of the human experience, as Svenaeus put it, is acutely exacerbated by illness. It also means that we use medical technology to remediate all kinds of problems that aren’t illnesses because those problems are experienced in and through our bodies - how could they not be? Those problems make our experience less our own, less homelike, and therefore pique our imaginations to consider how medical technology might help.

Consider, for example, abortion. US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg commented that “…legal challenges to undue restrictions on abortion procedures do not seek to vindicate some generalized notion of privacy; rather, they center on a woman’s autonomy to determine her life’s course, and thus to enjoy equal citizenship stature.” A medical procedure, in this line of reasoning, is integral to ensuring equality for all citizens (in this case, by making the life course of a woman more like a man’s by ensuring her freedom from the encumbrances of pregnancy). Setting aside the debate about the morality of abortion itself, it seems to be a remarkable development that a society requires a medical procedure to ensure equality for all its citizens. This medical procedure becomes not (only) an instrument to pursue health, but an instrument of justice. Something similar motivates the interventions Mathison and Davis describe. Healthcare is intimately bound up with matters of justice. This isn’t, in and of itself, good or bad, but the use of medical technology for these other purposes presents unique challenges. I’ve already written about what seems to happen when we divorce the use of a medical technology from its purpose in pursuing health, but we need to consider separately what it means to replace health with other goods like beauty or justice. Maybe I’ll venture down that rabbit trail another time.

For now, because of this totalizing effect of medical technology that tempts its use in all areas of life, let’s be careful with our questions. Is it good to use our health for any purpose we see fit? General ethics and the law declare that some things are off limits. I’m not allowed to murder or steal, for example; I’m not allowed to use my body and health for those purposes. There are limits on the ways in which I can use my health.

Is it good to use a particular technology on my body for any purpose I see fit? Justice is a consideration here also, for example in ensuring equitable distribution of the technology. This includes discerning how the pharmakon will influence its impact. There may also be wise and unwise uses, dignifying and degrading uses. Although a shared understanding of what those are would help us here, it need not inform from the outset whether we should use a medical technology. Might doesn’t make right; the majority shouldn’t foist their will upon the minority simply because they have power. This is the essence of liberal democracy, where even the majority must honor the rights of all. Any course of action must appeal to something deeper, which I’ll discuss in a moment. Furthermore, while my use of a particular technology may be a private affair and in the short-term only affect me, popular use will shape a culture in unanticipated and possibly undesirable ways. This may rise to such a level of concern so as to restrict individual access (e.g., recreational substance use).

Is it good for someone else, namely a clinician, to use technology to help me to do what I want with my body? This seems to merely rephrase the first two questions, for as long as the clinician’s values are aligned with my own, then the answer for me is the answer for them. But what if our values aren’t aligned? What if the clinician sees things differently than I do? How do we resolve the disagreement? Are clinicians conscienceless instruments in service to the will of their patients, or do they require the use of conscience to guide clinical decision-making as they bridge the gap from generalizable evidence to specific patient, even if it sometimes puts them at odds with their patients’ desires?

Is It Good?

At the root of these questions is some understanding of the good. That understanding can’t be entirely subjective. John Safranek explains why:

“The principle of autonomy or liberty requires a ‘harm’ principle to justify prohibiting certain types of autonomous acts, but whether an act is specified as harmful or harmless will depend on the preferred theory of good. Therefore the normative use of the principle of autonomy is performatively self-refuting: when scholars proscribe certain autonomous acts in the name of harm, or defend other autonomous acts judged harmless, they impose an axiology and subvert autonomy.

…

The justification of the act will hinge on the end to which autonomy is employed: if for a noble end, then it is upheld; if depraved, then it is proscribed. It is not autonomy per se that vindicates an autonomy claim but the good that autonomy is instrumental in achieving.”

Desires, values, or idiosyncratic notions of harm don’t provide a sufficient basis to guide medical practice. Autonomy, although serving a critical role in ethical deliberation, never has been and can’t be axiomatic. Current healthcare law and ethics, and Mathison and Davis in their paper, don’t suggest supporting a patient’s autonomy for mere autonomy’s sake either. There are constraints, as Tania Salem argued regarding physician authorization of assisted suicide and euthanasia:

“…someone other than the person requesting aid in dying has greater expertise in judging the appropriateness of that request. Medical authority, that is, is assumed to have the proper ability to unveil the ‘real truth’ behind the request to die.”

So Mathison and Davis task clinicians with discerning whether a patient is expressing a deeply seated value or a merely transient desire. The request must be reasonable in the clinician’s eyes. They readily admit, and I agree, that the goals of medicine, whatever they are and even if one goal is to promote the values of individual patients, are insufficient in themselves to guide clinical practice. We need additional information to act, and other constraints to keep us on the path.

Unwieldy and Lonely Tools

C.S. Lewis, writing in 1943, had a warning: “For the power of Man to make himself what he pleases means, as we have seen, the power of some men to make other men what they please.” This is the tantalizing promise of biomedical science: gaining control over all those hidden spaces within ourselves, we can finally be at home in our own existence. But when we think we’re controlling “nature,” we’re actually using nature to control other people. This is how cultures are transformed by a bunch of individuals doing similar things. Lewis argued that this flip happens when we try to get outside the Tao, his inclusive shorthand for “natural law,” “traditional morality,” “first principles of practical reason,” “first platitudes,” or the axiomatic basis for any of humanity’s value judgments:

“What purport to be new systems as … ‘ideologies’, all consist of fragments from the Tao itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation, yet still owing to the Tao and to it alone such validity as they possess.”

For Lewis, such attempts lead to the abolition of humanity because they’re self-refuting. They degrade the solid foundation on which we can establish any understanding of clear moral principles. This harms us as we come to view ourselves and others as mere nature to be manipulated.

You might say the individual is the axiom upon which we build our practice of medicine: what patients want, they get. But that isn’t the case, as Safranek, Salem, and others have argued, and even what Mathison and Davis concede. We must go further back - but to where? Lewis observed:

“You cannot go on ‘seeing through’ things forever. The whole point of seeing through something is to see something through it. It is good that the window should be transparent, because the street or garden beyond is opaque. How if you saw through the garden too? It is no use trying to ‘see through’ first principles. If you see through everything, then everything is transparent. But a wholly transparent world is an invisible world. To ‘see through’ all things is the same as not to see.”

Autonomy, on its own, is insufficient to provide guidance for the practice of medicine. We keep returning to it, though, because our hopes remain invested in a centuries-old project that stifles our imagination. We struggle to imagine another possibility apart from unlimited autonomy or crushing authoritarianism. Daniel O’Brien summarizes that history:

“During the European Middle Ages and until the political, social, and philosophical upheavals of the seventeen and eighteenth centuries, the church and (divine) monarch exerted near total authority over the populace. The populace had no political or intellectual tools to redress their subjugation because the institutions of the church and monarchy were, in addition to being the sole foci of political power, the gatekeepers of morality and of the distribution of the good for a human life (often defined as salvation following death, the promise of which was withheld from those unwilling to offer total political obedience). Any particular (subjugating) practice of the monarch or of the church was right because the church or the monarch willed it so, and the church and the monarch determined such things completely. The Enlightenment response to this schema was to attempt to locate the nidus of ethics and the good for man and woman not in institutions but in the individual himself or herself. Thus, various attempts were made to demonstrate that ethical conduct was determined by individuals acting (depending on the argument) in accordance with pure will, etc.”

The Enlightenment provoked a fundamental shift from the teleological ethics of the classical world to a relativized ethics grounded in the individual. After the Enlightenment, O’Brien observes, people have been free to define their purposes as they see fit: “Moral conduct … is not a pattern of behavior that directs one-as-one-is toward what-one-ought-to-become - there is no such entity as that which one ought to become. The rules of ethics or morality are not separate from the individual’s nature. They must issue from the individual himself or herself.” What I want is good; what I don’t want is bad. The customer is always right.

Severing health from the practices of medicine is one attempt to continue the broad work of this Enlightenment project to free the individual from the constraints of institutions. In so doing, we hope to give medicine to individuals to do with what they will. It doesn’t work out that way. In attempting to set ourselves up to do whatever we want, we actually become enslaved to our own techniques and technologies. This happens by destabilizing the practice of medicine in our already technical, technological milieu:

“When the practice and tradition of medicine are so off-kilter, we’ll lose a major way of managing all the information we gather when we care for folks. Rather than try to anchor ourselves back on health, we’ll apply technique more rigorously to become more efficient in managing the problems that keep cropping up as a result of this fever. On the one hand, we try to satisfy our patients’ desires, whatever those are. On the other, we work in a system bent toward efficiency that actually degrades and dehumanizes those very same patients (and clinicians). We want to care for the whole patient because we think knowing them better will allow a fuller realization of their autonomy. I worry that will just submit more of who they are to the machine we’ve built that lumbers and lurches further from health with each passing year.”

If, in our practice of medicine, we take our eyes off health, we don’t provide more opportunities to use medical technology for good. Rather, we provide more latitude for those technologies to form us in unexpected and likely undesirable ways. The answer isn’t in applying more technique to regain control over our instruments; it’s to situate the use of our instruments and practices in pursuit of a worthwhile, stable, coherent purpose.

So what am I proposing here - that we abandon respecting people’s autonomy? No, but I do think we need to better discern the relationship between autonomy and health. Individual values aren’t sacrosanct, as we’ve just seen. Clinicians and patients must work together to discern how those values inform the practice of medicine and if they’re constrained by ethical or logistical fences.

Farr Curlin and Christopher Tollefsen claim that “vocation” is what describes this use of health for individual value-laden purposes:

“We have made use of this account of vocation to argue for patient authority in healthcare decision-making. Patients have the authority to accept or refuse proposed interventions because they are in the best position to judge whether the benefits and burdens being offered to them are proportionate for them in light of their particular vocational commitments. The patient’s vocation provides the standard against which proportionality is judged.”

Ideally, clinicians are in a position to discern how medical technology can be used to support both the objective and subjective facets of health. Patients are in a position to judge how those interventions support their vocation (writ large, encompassing the entirety of their life and not just a particular activity). Importantly, “The patient can go wrong in assessing what her vocational commitments require, but still she has the best epistemic access to what those commitments are and what they imply for this medical decision.”

So whether it be sports surgery, contraception, living organ donation, elective cosmetic surgery, or something else, we act upon the human body because someone wants to use their health for a particular purpose. We can question whether those uses are wise or unwise, moral or immoral. Those are important, but separate, discussions. Part of respecting them as a person means respecting their authority to make decisions about how medical technologies will help or hinder them in pursuit of health. Part of respecting clinicians means respecting their capacities to discern the relationship between health and medical technology. These two forms of authority, one belonging to the patient and the other to the clinician, shouldn’t be in competition or tension with one another. Rather, they’re ideally synergistic in helping patients pursue health. Where there are disagreements, either at the bedside or in public debate, a compassionate appeal to wisdom and principle might help to persuade one or the other.

Trajectories

Following a meandering reading-path, sharing some brief commentary along the way.

“Exposing the technological roots of ambivalence”

Annie Friedrich expands helpfully on a paper I share frequently about ambivalence. Friedrich argues that because medical technologies, like all technology, are “multistable,” this induces significant ambivalence in its users. There isn’t just one way to relate to technology, or one right way. Friedrich lists several examples, but consider also how someone might relate to a ventilator: as a mere machine for moving air in and out of the lungs; as a savior; as a torture device; as a miracle; and so on. We want a medical technology’s promise of salvation with no “revenge effect” (the unintended and unforeseen consequences of its use). Friedrich recommends we attempt to overcome multistability-induced ambivalence through more and better questions. I don’t think multistability completely captures the formative influence of technology nor its impact on clinical decision-making, so Friedrich’s suggestions only get us part way there, but this is a helpful perspective.

“The Doctor’s Art: Lessons on Mortality and Dying Well”

Tyler Johnson and Henry Bair interview palliative care physician Ira Byock, whose wisdom extends way beyond palliative care to encompass all of medicine. He emphasizes that illness, injury, and death aren’t merely pathophysiologic conditions to be medically dealt with, but important experiences in a person’s journey through life. Clinicians need to recognize this so they don’t inadvertently dehumanize their patients.

“Death and the bogus contract between doctors and patients”

The bogus contract, as Richard Smith describes it, is an implicit arrangement between physicians and patients where patients believe physicians can do more than they really can, and physicians don’t disabuse them of that belief. There are many reasons for physicians shying away from this duty, but one that Smith doesn’t discuss is that some physicians are just as deceived as patients: they earnestly believe, or hope beyond belief, that they do have all that power (or rather, their medical technology does). If we call this what it is, we can take steps to remediate it: it’s either cowardice and arrogance, or naïveté. The solution isn’t as easy as what Smith suggests. Ironically, forcing patients to decide on their own without your recommendation may actually be a form of cowardice as you refuse to help patients and their families shoulder the existential burden of these terrible circumstances.

“Medical care needs more space for patient narratives”

Agnes Arnold-Forster tells a story of her own chronic illness and struggled to find care in a system that supposedly offers healthcare. She makes the plea that clinicians need to make space to listen to the stories of their patients. It struck me, reading this: many clinicians sub-specialize so they can more reliably depend on technology rather than patients’ stories to diagnose and manage problems. Some clinicians even long for the day when we have some kind of test to tell if someone is “really” in pain (rather than just asking them). What these clinicians fail to realize is that a lot of what we do is help our patients write and rewrite their stories of health and illness in ways that make sense to them. Howard Brody made the point that when patients come to us, they bring not just their broken bodies, but their broken stories. For clinicians who miss this, they become bad, even harmful, co-authors.

“Why and how to avoid therapeutic lying to people with memory loss”

Confronting incorrect beliefs and abnormal behaviors in people with dementia can be really challenging. One approach some clinicians recommend, and caregivers often discover on their own, is therapeutic lying: just go all in with the person with their belief that their mother is still alive or that they’re going to work in the morning. The therapeutic lie reveals that our primary motivation for telling the truth is to be believed; if someone won’t believe you or it will exacerbate their behavior, why tell the truth? But that discounts the power our words can have in creating our shared environment. I much prefer the approach recommended her: validating the underlying desire, value, or emotion without lying. It honors the person and doesn’t force you to lie.

“Analysis of physicians’ probability estimates of a medical outcome based on a series events”

The title describes a common scenario in medicine and the authors provided study participants some clinical scenarios in which they were asked to predict the probability of the final outcome. Many folks prognosticated that the probability of the final outcome was greater than the probability of any event in the series - an impossibility. “In response to these issues, several researchers have recommended including greater emphasis on numeracy as well as statistical and probabilistic reasoning in medical education.” I agree, and add to the list education in decision-making, cognition, and communication as well. I do wonder if an adjustment helps to limit this bias: providing one’s prognostication in narrative, rather than quantitative terms - e.g., best case/worst case/most likely case scenario planning. Furthermore, providing the upper and lower limits of possibility may help the clinician to more realistically appraise what they think is the most likely case scenario.

Closing Thoughts

“In clinical pharmacology, contemporary technology plays a dominant role in shaping ideology. What we look for in patients depends to a great degree on the available medications. That Tess's depression was accompanied by what could be construed as compulsiveness was of interest only because this trait might be an indicator of something we could now treat. Who Julia is--whether she is a fully functional woman with marital troubles or a slightly handicapped woman adjusting uncomfortably to reasonable constraints--is largely a function of drug development. We may decide on similar grounds whether Tess’s dedication is a moral or a psychopathological trait. How we, as observers of our fellow men and women, look and listen, how we categorize, how we understand the tensions between people and their predicaments, is in part a product of the available means of influence.”

Peter Kramer, Listening to Prozac

I don’t prefer the term “autonomy” but I’m using it as many people are familiar with it. Autonomy implies a kind of atomized individual who acts free from constraint that doesn’t exist in real life. Relational autonomy is more realistic, but I prefer the term “agency.” There are nuanced debates in the semantic weeds about the differences among these terms, but suffice it to say, what I want to convey is responsibility for self-governance which is necessarily socially conditioned and embedded.