In The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis describes a textbook for teaching grammar to older age school children. “I doubt whether we are sufficiently attentive to the importance of elementary text books,” he begins, but then goes on to write of the authors, “I shall have nothing good to say of them.” The topic Lewis chooses to start one of his most profound books of non-fiction is so mundane that you might be tempted to sit it down. If we persevere, though, we find the malignant hiding behind the mundane.

The Green Book, as Lewis calls it, sneaks in a way of looking at the world that is so formative, so foundational in students’ thinking, that they won’t even remember how they learned it as they grow older. What, you might ask, is this book doing? Reflecting on a story about two tourists sharing their feelings about a waterfall,

“Gaius and Titius [the pseudonyms Lewis gives to the authors] comment as follows: ‘When the man said This is sublime, he appeared to be making a remark about the waterfall…Actually…he was not making a remark about the waterfall, but a remark about his own feelings. What he was saying was really I have feelings associated in my mind with the word “Sublime”, or shortly, I have sublime feelings.’ Here are a good many deep questions settled in a pretty summary fashion. But the authors are not yet finished. They add: ‘This confusion is continually present in language as we use it. We appear to be saying something very important about something: and actually we are only saying something about our own feelings.’”

What’s the big deal with this? Bear with the extended excerpt:

“The schoolboy1 who reads this passage in The Green Book will believe two propositions: firstly, that all sentences containing a predicate of value are statements about the emotional state of the speaker, and secondly, that all such statements are unimportant. It is true that Gaius and Titius have said neither of these things in so many words. They have treated only one particular predicate of value (sublime) as a word descriptive of the speaker’s emotions. The pupils are left to do for themselves the work of extending the same treatment to all predicates of value: and no slightest obstacle to such extension is placed in their way. The authors may or may not desire the extension: they may never have given the question five minutes’ serious thought in their lives. I am not concerned with what they desired but with the effect their book will certainly have on the schoolboy’s mind. In the same way, they have not said that judgements of value are unimportant. Their words are that we ‘appear to be saying something very important’ when in reality we are ‘only saying something about our own feelings’. No schoolboy will be able to resist the suggestion brought to bear upon him by that word only. I do not mean, of course, that he will make any conscious inference from what he reads to a general philosophical theory that all values are subjective and trivial. The very power of Gaius and Titius depends on the fact that they are dealing with a boy: a boy who thinks he is ‘doing’ his ‘English prep’ and has no notion that ethics, theology, and politics are all at stake. It is not a theory they put into his mind, but an assumption, which ten years hence, its origin forgotten and its presence unconscious, will condition him to take one side in a controversy which he has never recognized as a controversy at all. The authors themselves, I suspect, hardly know what they are doing to the boy, and he cannot know what is being done to him.”

Lewis reflects that what’s happening here, whether Gaius and Titius intend it, is a paradigm shift: “Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.”

He goes on to describe various perspectives - ranging from Aristotle to Hinduism to Augustine to the Tao, all seeing an objective link between one’s emotions and reality. He ultimately adopts the latter title for what he describes as…

“…the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, to the kind of thing the universe is and the kind of things we are. Those who know the Tao can hold that to call children delightful or old men venerable is not simply to record a psychological fact about our own parental or filial emotions at the moment, but to recognize a quality which demands a certain response from us whether we make it or not.”

When it comes to educating school children or, say, medical students, one can approach the work from inside or outside the Tao:

“For those within, the task is to train in the pupil those responses which are in themselves appropriate, whether anyone is making them or not, and in making which the very nature of man consists. Those without, if they are logical, must regard all sentiments as equally non-rational, as mere mists between us and the real objects. As a result, they must either decide to remove all sentiments, as far as possible, from the pupil’s mind; or else to encourage some sentiments for reasons that have nothing to do with their intrinsic ‘justness’ or ‘ordinacy’. The latter course involves them in the questionable process of creating in others by ‘suggestion’ or incantation a mirage which their own reason has successfully dissipated.”

The Abolition of Medical Education

With the springboard of Lewis’s words underneath us, we can dive into what this means for medical education. I’m a physician and am in a better position to comment on education for medical students, but maybe this applies elsewhere to nurses, physical therapists, and the like.

There’s no textbook that medical students read like The Green Book. Heck, there’s no textbook that medical students read. They venerate certain books (e.g., Harrison’s Internal Medicine), but they don’t imbibe them. Medical education has its own forms of The Green Book, though, where important moral lessons are slipped in while students are busy doing other work. This is, as Frank Hafferty called it, the hidden curriculum: “a set of influences that function at the level of organizational structure and culture.” When people think about the hidden curriculum in medicine, they might consider sidebar conversations in the workroom that inculcate certain values, often negative, about how we perceive ourselves as clinicians and others as colleagues or patients. The laws of the House of God capture this ethos. If you don’t take a temperature, for example, you can’t find a fever. We can leave certain questions unasked if the answers are inconvenient.

But the hidden curriculum doesn’t begin with the clinical rotations in medical school. It starts earlier, as students memorize the Krebs cycle and struggle through standardized exams. Hafferty observes that a major task of becoming a doctor (or any clinician, really) is separating what’s important from what’s not important. It’s a value-laden exercise. The way medical education is currently framed, this bends toward a biologically reductionistic, gamified set of priorities. Is this going to be on the test? Is this going to budge the creatinine? Is this going to get the patient discharged?

There’s a lot to learn in medical training. Medical school can feel like a massive transfer of information. As the formative influence of the hidden curriculum demonstrates, though, it would be a mistake to believe that medical trainees are merely “heads on sticks” - all brain, all rationality. The mental health and burnout crisis is helping to awaken educators to the reality that medical trainees are whole people, but that hasn’t yet reached the basics of medical education.

Lewis argues that not only does a person have a brain, they also have a “belly,” which are those urges and appetites that drive them toward food, power, comfort, and sex. There’s also a mediator between head and belly: the chest. “The head rules the belly through the chest - the seat … of Magnanimity, of emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments. … It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal.”

Insofar as this relates to education, it means that people aren’t argued into virtue. One becomes virtuous by training one’s emotions. Augustine knew this: virtue is loving things in the right priority. Aristotle too: we should teach students to like or dislike those things that are right and good to like and dislike. Most religions acknowledge this as well. The Green Book has its own way of teaching this by asserting there’s nothing more substantial to emotions than private preference.

The world of medicine has its codes of ethics, but these aren’t as formative as the hidden curriculum. And even if medical schools are slowly adding courses on ethics and humanities into the curricula, residencies in large part lack ongoing training in these. This “null curriculum” affirms what all the standardized testing throughout training leads trainees to believe: the real work of medicine is in pharmacology, surgery, stents, and so forth. Even when medical students are offered opportunities to learn more about the broader human experience of suffering and illness, for every ten hours spent studying the Krebs cycle, they might spend one minute engaging these other topics.

An Education in Technique

Saul Weiner and Stefan Kertesz, on their podcast On Becoming a Healer, discuss a recent NYT article entitled, “When Doctors Use a Chatbot to Improve Their Bedside Manner.” They conclude that this isn’t good. What is driving physicians to rely on a chatbot to gin up what should instead arise organically from a caring, human relationship? Nevertheless, they seem to admit that a “fake it til you make it” approach may be valuable: use the canned phrases meant to demonstrate you care until you really do care. This is probably the kind of technical response that collapses the “chest” Lewis was so concerned about, but it need not be. Even if you don’t care, you need to want to care and, ironically, that is a form of inchoate caring. If you go through the motions wanting to care, there’s hope you may find yourself caring more deeply. For someone doesn’t even want to care, going through the motions of caring will only further ossify their technical posture.

Technology, canned phrases and illness scripts included, uses us. In the words of Frankenstein’s creature: “Remember that I have power; you believe yourself miserable, but I can make you so wretched that the light of day will be hateful to you. Your are my creator, but I am your master. — Obey!” Words themselves are a technology that can “bind and blind us,” to borrow the words of Jonathan Haidt. Words bind us to particular communities and courses of action, and they shape the way we see (or don’t see) the world. This is the power of the hidden curriculum. Resisting it without good models and mentors can feel like holding a candle against the wind, so we hope more technique will save us. Enter GPT.

But using technology in this way misses the mark. We want clinicians who care about us, not because they’re told to do so or because it will get them the approval of others, but because their thoughts and behaviors are invigorated by real compassion. It goes beyond the bedside, though. When professions yield their consciences to bureaucracy (whether it by the state or another entity), they become mere instruments of that larger body. This happened in Germany in the early 20th century. Clinician virtue provides a check on the political intentions others might have for medical interventions. Without such virtue, clinicians are reduced to their heads and bellies. Viewing clinicians as all head, we see medicine as technique, and we worry that artificial intelligence might replace us. Feeling the urges of our bellies, we ache with moral distress we don’t know how to assuage. Attempts of the “head” to control the “belly” unmediated through the virtuous influence of the “chest” result in more techniques to further constrain the emotional lives of clinicians, exacerbating the problem.

What has happened in medicine is a microcosm of what’s happened in broader Western society. One of the advantages of liberalism has been to uphold the freedom of the individual to chart a course of their own life. One of the disadvantages has been the erosion of thick forms of community that provide us with meaningful content for roles, duties, and relationships. This tension between the individual and the community is ancient, ever-present, and insurmountable. Professions like medicine, law, education, and the clergy have been bastions where this tension has been sustained in ways that sometimes contribute to flourishing, but that’s changing.

Warren Kinghorn, Matthew McEvoy, Andrew Michel, and Michael Balboni reflect on the irony of cultivating virtue in medical practice: “If students have already cultivated these virtues within a living moral community, formal education in medical professionalism may be largely unnecessary. If they have not cultivated these virtues, professionalism education is necessary but, unfortunately, often ineffective.” This means “any effective moral education of students should acknowledge that moral formation occurs primarily through participation in moral communities and only secondarily through discursive reasoning.” In short, you’re not argued into virtue.

What they recommend is engagement with “open pluralism: a commitment to explore, understand, and hear the voices of the particular moral communities that constitute our culture.” A curriculum of such open pluralism “would invite (particularly minority) cultural and religious leaders to address students and trainees about the particularities of their moral communities. It would also encourage respectful, charitable discussion regarding the value of the moral commitments of those communities. Students would be encouraged to acknowledge, explore, and critically examine their own a priori moral convictions, allowing for the recognition of orienting and substantive narratives out of which profession and professional duty can flow.”

The devil’s in the details, though. As you might imagine, I’m concerned that a medical curriculum grounded in technique and efficiency will co-opt this initiative toward that purpose, rather than cultivating thick community with a coherent moral basis. Ironically, even if we do all that Kinghorn and his colleagues recommend, we can do it in a spirit of technique; such open pluralism can become yet another technical initiative among many. Perhaps what’s needed isn’t just that the medical educators reach out to these moral communities, but also that leaders within these moral communities reach in to the world of medicine to testify to a better way of seeing the world and other people.

In That Hideous Strength, the third in a science fiction trilogy by Lewis, he tells a story of an organization that has reanimated a decapitated head. This excerpt is from a discussion among a resistance party reflecting on what this means:

“‘…if this technique is really successful, the Belbury people have for all practical purposes discovered a way of making themselves immortal.’ There was a moment’s silence, and then he continued: ‘It is the beginning of what is really a new species - the Chosen Heads who never die. They will call it the next step in evolution. And henceforward, all the creatures that you and I call human are mere candidates for admission to the new species or else it’s slaves - perhaps it’s food.’”

Elsewhere, the reader gains an appreciation for what it actually means for this organization to reanimate the head and the head alone. Here is one of the insider’s describing the vision:

“You are to conceive the species as an animal which has discovered how to simplify nutrition and locomotion to such a point that the old complex organs and the large body which contained them are no longer necessary. That large body is therefore to disappear. Only a tenth part of it will now be needed to support the brain. The individual is to become all head. The human race is to become all Technocracy.”

True to science fiction, there’s an element of unbelievability. The content of the story is ridiculous: reanimating a head! And not only that, but an organization with grand aspirations to reduce all of humanity to disembodied heads (and really, brains). But there’s also a question that haunts the perceptive reader even after they sit the book down: why not? If we’re on an inexorable march toward mapping the brain, and the brain is the seat of what really matters, then why not? Writ smaller and more realistically, does this not capture our hope for artificial intelligence? That Hideous Strength brings us to ask, just as other stories like Klara and the Sun, whether there is anything in us that can’t be reduced to machine.

Trajectories

Following a meandering reading-path, sharing some brief commentary along the way.

Michael Sacasas reflects on how these two concepts are different. He focuses on parenting, but you and I know it that his remarkable observation applies to the world of medicine too. “Care implies a form of patient and deliberate seeing. Maybe care simply is that kind of seeing, or perhaps it is more modest and reasonable to say that care is grounded in such seeing. So the outsourcing of our seeing, of our notice, of our attending vision already precludes the realization of care.” Properly using healthcare technology means practicing both with the end and the subject in mind.

As Mildred Solomon steps down as president of The Hastings Center, she shares these words about the tension between the individual and the community. Because Solomon starts her history in the mid-20th century, with the inception of modern bioethics, she isn’t able tot comment on the ancient roots of this tension. Plato’s Republic discusses the relationship, for example. But you need not go back that far. Look at how Germany resolved the tension in the early 20th century. Their’s was an extreme form of paternalism against which modern bioethics was a reaction, but it was also an extreme form collectivism. It had a totally different anthropology than the liberalism with which we are so familiar in the USA today. Modern bioethics, including law, enfolded the individual with robust protections to guard against such a disaster ever happening again. But now we veer into a different ditch which is the focus o Solomon’s essay: collective-impact problems, like pandemics and climate change. She advocates for a renewed appreciation for justice and public engagement. However, how can we turn on a dime just because there’s a crisis after spending 50+ years of “respect for autonomy“ (swerving, at times, into “the customer’s always right”)? We’ve been prepared to meet these crises in certain ways. Arguments and essays won’t change that, and so Solomon’s appeal rings empty. What’s needed are thick forms of community. The tension between the individual and the community will always be there. To resolve it one direction or the other is to invite disaster. But in order to sustain the tension toward flourishing, we need to appreciate those capacities that enable us to both pursue things that contribute to such flourishing, and sustain communities that can cultivate such capacities. Without such virtue, we face an endless appeal to power.

I’m a big fan of the best case/worst case framework for describing treatment options. It’s much better than throwing a bunch of numbers about burdens and benefits at someone, and helps the clinician to tailor prognoses to things about which the patient actually cares. Here’s an example of its application to heart failure (specifically LVAD vs supportive care).

“Bloated patient records are filled with false information, thanks to copy-and-paste”

A confession: I copy-and-paste. Specifically, I copy-and-paste my group’s manually drafted medical and social histories (because the auto-populated medical history is fraught with useless information and is difficult to update), as well as the plan (with appropriate updates). But I’ve seen the fallout of less judicious uses of copy-and-paste. It makes some notes unreadable. People have been calling for changes to this culture for years and no change is forthcoming. Now some are hoping artificial intelligence will save us from the albatross of note bloat - either by crafting better notes or by reviewing the bloated chart. The belief that more technology will save us from the burdens of technology is the essence of technopoly. We need to change our practice of medicine first.

Closing Thoughts

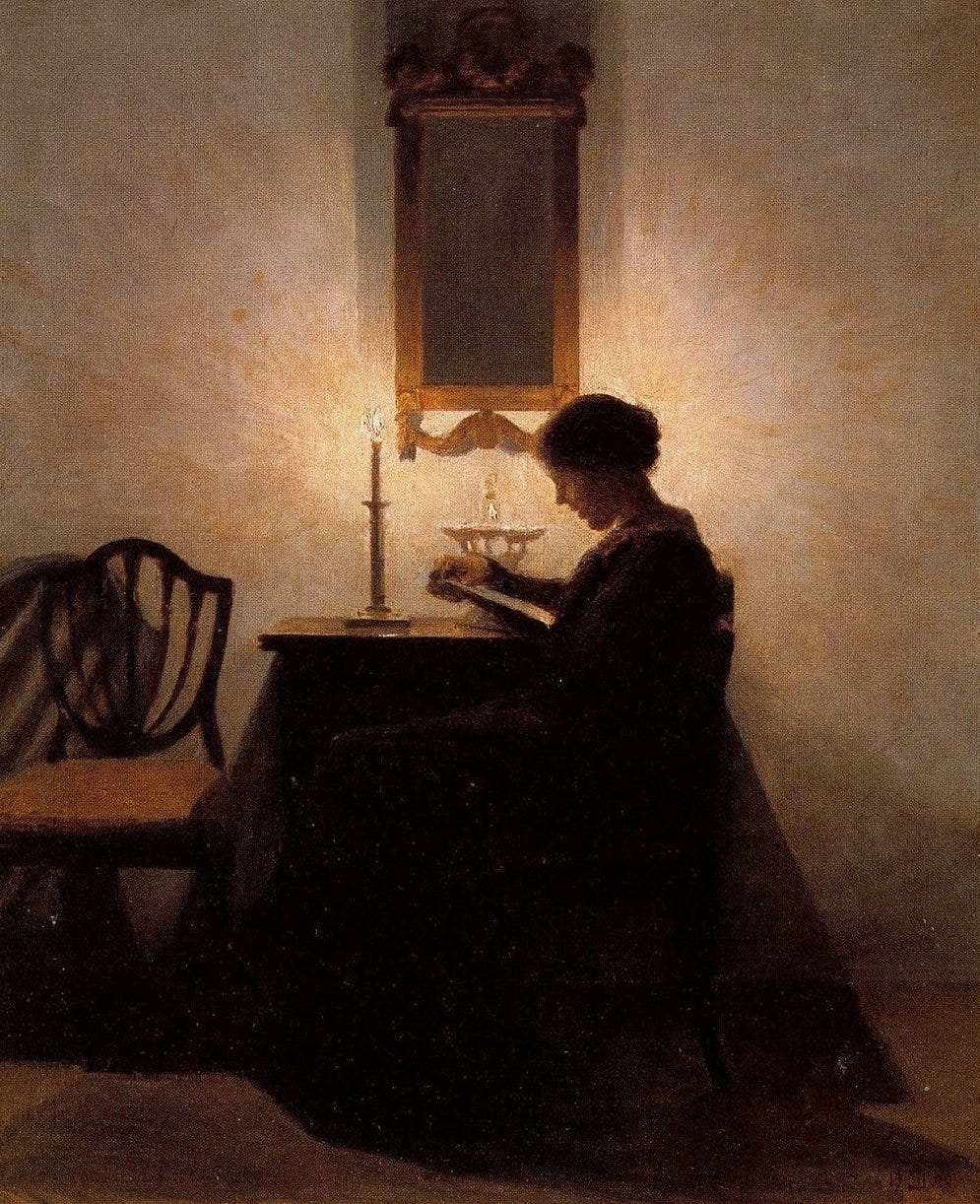

Sundays too my father got up early and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold, then with cracked hands that ached from labor in the weekday weather made banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him. I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking. When the rooms were warm, he’d call, and slowly I would rise and dress, fearing the chronic angers of that house, Speaking indifferently to him, who had driven out the cold and polished my good shoes as well. What did I know, what did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices?

Robert Hayden, “Those Winter Sundays”

Throughout the work, Lewis uses male pronouns and masculine words, which was consistent with his time. Here he means “school children,” not just boys, and in most other places “man” refers to humanity as a whole.